By Christopher Allen & Shannon Appelcline

[This is the third in a series of articles on collective choice, co-written by my collegue Shannon Appelcline. It will be jointly posted in Shannon’s Trials, Triumphs & Trivialities online games column at Skotos.]

In our first article on collective choice we outlined a number of different types of choice systems, among them voting, polling, rating, and ranking. Since then we’ve been spending some time expanding upon the systems, with the goal being to create both a lexicon of and a dialogue about systems for collective choice.

This time we’re going to dig more into comparison ranking systems, by focusing on competitive rankings and looking more in depth at ELO Chess Ranking System and the other systems that we briefly mentioned previously. Our goal is to explicate these systems, to better address their flaws, to begin detailing the purposes of ranking systems, and to show how those purposes are critical in the design of ranking systems.

Subjective vs. Objective Rankings

In our original article we discussed rating systems as being largely subjective and ranking systems as being objective, but the situation isn’t nearly as simple as that. In truth, there’s a clear spectrum of ratings and rankings with varying amounts of subjectivity and objectivity in each collective choice system.

(BCS) for college football is a good example of a ranking system that explicitly allows a subjective component. It involves a complex mathematical formula that includes things like win/loss ratios, but also sportswriters’ and coaches’ ratings.

(BCS) for college football is a good example of a ranking system that explicitly allows a subjective component. It involves a complex mathematical formula that includes things like win/loss ratios, but also sportswriters’ and coaches’ ratings.

However, public opinion continues to show that people don’t necessarily like seeing true ranking systems having subjective components, because they expect them to be “fair”. The BCS formula has come under attack several times in the last few years precisely due to its subjective basis. Cal Berkeley was one of several teams denied a bowl position in 2004 when many felt that they were worthy.

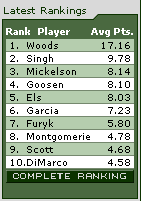

The APL tennis rankings and the official world golf rankings also have a subjective component, but it is much more subtle. Each tournament is worth a certain number of points, and the allocation of those points is relatively arbitrary, based upon the “prestige” of each tournament and the quality of players who have traditionally played in it. The subjectivism isn’t quite as near to the surface as that of the college bowls, but it’s still something that can have a notable, and perhaps unwarranted, effect upon the final results.

Algorithmic Rankings

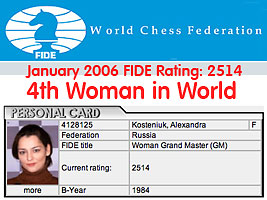

This brings us back to the ELO system, a ranking system originally designed for chess which is fairly well-known and well-understood. As we said in our overview article, “[ELO] builds a simple distribution of player ratings around a norm (typically 1500 points), then awards or deducts points based upon wins and losses, with the total sum of all points in the system staying constant. Players are then ranked according to their comparative scores.”

This brings us back to the ELO system, a ranking system originally designed for chess which is fairly well-known and well-understood. As we said in our overview article, “[ELO] builds a simple distribution of player ratings around a norm (typically 1500 points), then awards or deducts points based upon wins and losses, with the total sum of all points in the system staying constant. Players are then ranked according to their comparative scores.”

The big difference between this and the previously discussed systems is that it’s almost entirely objective; in fact it uses a statistical basis to create an underlying mathematical model for rankings, rather than allowing human subjectivity to get in the way.

The simplest formulation for an ELO rating looks like this:

R' = R + K * (S - E)

R'is the new rating

Ris the old rating

Kis a maximum value for increase or decrease of rating (16 or 32 for ELO)

Sis the score for a game

Eis the expected score for a game

Much of the trick is in figuring out what the (E)xpected score of a game is. ELO uses the following formulas for players A and B:

E(A) = 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ ( [R(B) - R(A)] / 400 ) ]

E(B) = 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ ( [R(A) - R(B)] / 400 ) ]

It’s a good model because, using the two formulas, it means that a great player gains little from beating an average player, but an average player gains a lot from beating a great player. Take the following example:

R(A) = 1900

R(B) = 1500

E(A) = 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ ( [1500 - 1900] / 400 ) ]

= 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ ( -400 / 400) ]

= 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ -4 / 4 ]

= 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ -1 ]

= 1 / 1 + .1

= .91

= 91%E(B) = 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ ( [1900 - 1500] / 400) ]

= 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ ( 400 / 400 ) ]

= 1 / [ 1 + 10 ^ 1 ]

= 1 / 11

= .09

= 9%

Player A is expected to score .91 in an average game, which is to say he should win 91% of the time, and will be punished accordingly if he loses to player B:

R’ = 1900 + 32 * (0 - .91)

R’ = 1900 - 29.12

R’ = 1871

Conversely a win nets him very little:

R’ = 1900 + 32 * (1 - .91)

R’ = 1900 + 32 * .09

R’ = 1900 + 2.88

R’ = 1903

ELO is almost entirely mathematical. Players can gain or lose different amounts of points based upon playing different players, but this is all part of the formula. The only slightly subjective element is the definition of K -- how much a player can win or lose from a particular game. The most widely used ELO systems for Chess break K down into two values: 16 for masters and 32 for everyone else. So there is a subjective decision that masters should vary their score less frequently than other players.

That’s a very minor element in an otherwise objective system, but as we’ll see, more recent systems by Days of Wonder and Microsoft first reduce, then eliminate even this subjectivity.

Variations of a Theme: Days of Wonder

ELO is probably the most used ranking system in the world. You can find it in use for Go, Tantrix, and many other games. Days of Wonder, producers of Gang of Four, Ticket to Ride, and many other games use a variant of the system which they describe on their website.

ELO is probably the most used ranking system in the world. You can find it in use for Go, Tantrix, and many other games. Days of Wonder, producers of Gang of Four, Ticket to Ride, and many other games use a variant of the system which they describe on their website.

They identify three core problems with ELO:

- New players can take a long time to ascend or descend to their correct levels.

- Highly ranked players can be hesitant to play with provisional players whose ranking might be much more uncertain.

- There are no allowances for games with more than two players.

Days of Wonder resolved the first problem by creating a new formula for provisional players, allowing them to rise and fall in the rankings much more quickly.

Conversely when playing against provisional players, regular players can only lose a maximum of K*n/20 points, where n is the number of games that the provisional player has played–rather than the normal maximum loss of K. For example, playing someone who has just played one game, can only result in a loss of 1/20th of the regular K value, and so it really doesn’t matter if the provisional player’s ranking is wildly out of whack.

Both of these new formulas are set up to converge toward a normal ELO formula as a provisional player’s number of games approaches 20 (making them a normal player at Days of Wonder).

(It should be pointed out that using the number “20” to define a provisional player, and making a player less provisional in clean 5% steps, inevitably offers yet another small, subjective element into this mathematical formula; as we’ll see momentarily Microsoft has more recently incorporated the idea of provisional uncertainty into their core mathematical model, much as the whole ELO system originally turned subjective win and loss statistics into tighter mathematics.)

Finally, to resolve the situation of multiple players, Days of Wonder considers each game to be a set of duels, as described here:

There are 4 players in a Gang of Four game. Let’s name A the winning player, B the second one, C the third one and D the last one. We consider that there were 6 duels: A won against B, C and D. B won against C and D. C won against D. We compute independently the new scores for each duel, and then we average the values for each player.

It’s a fairly elegant answer that not only rewards or penalizes all players separately, but also encourages playing for second place, or even third, if first isn’t possible.

There have been continued discussions of the Days of Wonder ELO variant in their forums, and the questions raised there are common to many different ranking systems. Some players wanted unranked games, while others thought that having unranked games would discourage people from playing good competitors except in unranked games. There has also been a lot of discussion regarding Ticket to Ride, a strategy game that supports 2-5 people, and whether the ELO variant system discourages multiperson play.

The various lessons learned at Days of Wonder underline two basic ideas about rankings. First, even with a well-studied system like ELO, there’s still a lot to understand, and, second, any ranking system needs to reflect the specifics of what it’s ranking – and what its purpose is.

Variations on a Theme: XBox 360 Live

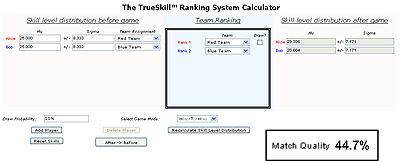

An even more recent large-scale ranking system is the TrueSkill system developed by Microsoft for use with the XBox 360. It appears to be an expanded variant of the glicko ranking system used by the free internet chess server.

An even more recent large-scale ranking system is the TrueSkill system developed by Microsoft for use with the XBox 360. It appears to be an expanded variant of the glicko ranking system used by the free internet chess server.

Many of the problems identified by Microsoft were the same as those already noted by Days of Wonder and others, including: the uncertainty of provisional ratings and the need to rank players in multiplayer games. However, the TrueSkill system notably expands both issues. Ranking uncertainty is now defined as a mathematical concept and the rankings now support not just multiple players, but also multiple teams.

TrueSkill explicitly includes two values in any ranking: a skill level and an uncertainty level. The first, like the more common ELO ranking, tells how good a player is. The second states how sure that ranking is. The uncertainty rating is effectively a margin of error, similar to those we saw in polling systems. If a first-time player has a skill rating of 25 with an uncertainty rating of 8.3 that means that his skill is probably somewhere in the range of 16.7 to 33.3, a pretty wide range, but then this is a totally untested player. According to benchmarks that Microsoft produced, 99.99% of actual skill levels were within 3x of the uncertainty rating, and 100% were within 4x.

TrueSkill explicitly includes two values in any ranking: a skill level and an uncertainty level. The first, like the more common ELO ranking, tells how good a player is. The second states how sure that ranking is. The uncertainty rating is effectively a margin of error, similar to those we saw in polling systems. If a first-time player has a skill rating of 25 with an uncertainty rating of 8.3 that means that his skill is probably somewhere in the range of 16.7 to 33.3, a pretty wide range, but then this is a totally untested player. According to benchmarks that Microsoft produced, 99.99% of actual skill levels were within 3x of the uncertainty rating, and 100% were within 4x.

The rest of TrueSkill’s innovations are built around this model of uncertainty. All players win or lose skill points, based upon how many players they beat or lose to, and they also decrease their uncertainty rating as they play more games. However, uncertainty is decreased more for players toward the middle of a pack within a game than those around the edges (because on the edges the players could actually be much better or much worse than it is possible to see from a specific game). In addition, TrueSkill is only a zero-sum ranking system for players at the exact same level of uncertainty. The more uncertainty that an opponent possesses, the smaller the weighting of any gain or loss (much like the simpler system that Days of Wonder uses, which bases weightings of games against provisional players as n/20).

Overall TrueSkill is a somewhat complex system that is described more fully at Microsoft’s web site. Some of their expansions had already been considered by others, but still their system is notably innovative in two ways:

-

Expanding a competitive ranking system to include concepts of teams.

-

Incorporating the uncertainty of ratings further into the core mathematical model, rather than using a somewhat more subjective model such as that described by Days of Wonder for provisional players.

The TrueSkill calculations are a bit complex. In general, that’s not a problem for a computer-based ranking model because you can have a computer doing all the computations, and players only need to understand the results. However the two-part ranking system used by TrueSkill, which notes both skill level and uncertainty, does offer a potential problem on this latter point. Can players understand it? In general, the concept of uncertainty will not be understood by people other that statisticians, thus raising a real user-interface question with the TrueSkill system – and the exact sort of thing that designers of new ranking systems will need to consider.

The TrueSkill calculations are a bit complex. In general, that’s not a problem for a computer-based ranking model because you can have a computer doing all the computations, and players only need to understand the results. However the two-part ranking system used by TrueSkill, which notes both skill level and uncertainty, does offer a potential problem on this latter point. Can players understand it? In general, the concept of uncertainty will not be understood by people other that statisticians, thus raising a real user-interface question with the TrueSkill system – and the exact sort of thing that designers of new ranking systems will need to consider.

Variations on a Theme: A Tale in the Desert

The online game, A Tale in the Desert, identified a different problem with the ELO system: cheating. This is a uniquely Internet-based problem, because there users can create fake accounts, then defeat those accounts to win points. This can also be done more subtly, by having multiple additional accounts build up the rating of that fake account before the fake account is defeated. So a totally new ranking system, called the eGenesis Ranking System, was created.

The online game, A Tale in the Desert, identified a different problem with the ELO system: cheating. This is a uniquely Internet-based problem, because there users can create fake accounts, then defeat those accounts to win points. This can also be done more subtly, by having multiple additional accounts build up the rating of that fake account before the fake account is defeated. So a totally new ranking system, called the eGenesis Ranking System, was created.

Each player is ranked through a 256-bit vector, half of which is initially set to 0 and half of which is set to 1 (therefore creating an average ranking of 128). Whenever a match occurs between players a hash function based on the players’ names mathematically selects 32 of those bits, 8 of which are then randomly selected. Among those bits, any 1s in the loser’s vector which correspond to 0s in the winner’s vector are “transferred”.

This simple design corresponds in some ways to ELO’s more complex formula. A good player will have more 1s and thus more to lose, and he will lose correspondingly more to a poor player who has more 0s in his vector.

However, the system also prevents the collusion earlier noted. Statistically, a single player will only ever gain 8 ranking points from another new player, since out of the 32 bit hash only eight of those will, on average, be in the correct 0-1 configuration. Expanding a group of players expands the number of points that can potentially be gained, but within real limits.

In fact, the eGenesis system prevents cheating by measuring the size of social networks, then limiting the number of ranking points that can be earned within a social network. It’s not necessarily the only way to measure social network size, but its methodology points toward social software as an interesting area for additional study of ranking systems.

In fact, the eGenesis system prevents cheating by measuring the size of social networks, then limiting the number of ranking points that can be earned within a social network. It’s not necessarily the only way to measure social network size, but its methodology points toward social software as an interesting area for additional study of ranking systems.

As with XBox’s TrueSkill, the eGenesis algorithms are overall fairly sophisticated and confusing, perhaps more so than TrueSkill itself. However, unlike TrueSkill the output is very simple: a skill number between 0 and 255. The intricacies are hidden by the system.

Competitive Ranking Goals

Ultimately, as we mentioned when discussing Days of Wonder, any ranking system has to be measured by what it’s trying to do and how well it does that. ELO and similar numerical, long-term ranking systems, are most likely trying to achieve one of three goals:

Hierarchy: Players are divided into hierarchies of success, giving players goals to constantly strive for and ways to measure their success (or failure).

Matching: Players can play with other players at their same skill level, rather than having to play beginners or experts who are much better than they are. This generally increases everyone’s enjoyment. For computer games, the complexity of a matching system can be largely moderated by the computer, thus ensuring better competition.

Handicapping: If players do play against others of different skill levels, the better players can be handicapped in automatic, appropriate ways for the game in question, again increasing the fairness of games and everyone’s enjoyment. For instance, someone ranked 3-kyu in Go playing a less experienced 7-kyu player would give him a starting 4 stone advantage to make for better competition.

The ELO system may be a good matching system, which allows players to easily find other players of their same skill level and play against them. However it doesn’t provide any way to handicap players, nor would the ELO method necessarily be a good one to analyze handicaps (and conversely a golf handicap might not do a good job of finding like players nor measuring players’ ability in a hierarchy).

More recently the XBox system has stated that it’s explicitly for matchmaking, with the goal being to always try and match up players at nearly the same skill level. It’s also used for hierarchy (or “leaderboards” as it’s described in the TrueSkill docs), but that’s clearly a subsidiary purpose.

All of these systems would be ineffective for measuring a winner in a live event, which is a very different goal:

Tourney: A single player is listed as an absolute winner, the “King of the Hill”. Often, second, third, and fourth place winners are measured too.

And, the systems we’ve discussed thus far may not be useful for measuring privileges, yet another goal:

Threshold: The best ranks of players can be given special privileges, including the ability to create games and form tournaments. Alternatively, they can be given privileges totally outside the game, again giving them something extra to strive for.

For each of these additional goals we may need to consider very different ranking systems, not just variations of ELO.

Different Themes: Tourneys

There are a number of well-known tournament types which can be used to create a “King of the Hill” ranking.

There are a number of well-known tournament types which can be used to create a “King of the Hill” ranking.

The simplest is the single-elimination tournament, where the winner of each competition moves on to compete with other winners, until there is only one. However, this style of tournament is quite cut-throat and is not suited very well to events where the competition may result in a draw, or where chance is a notable factor in the competition. It also has a very subjective factor in the initial seeding of the rounds. The single-elimination tournament also does not rank the losers. However, by having the losers compete with each other in a Swiss-style tournament, the relative strengths of the players can be ranked.

An improvement is the double-elimination tournament which is now one of the best known tournament systems in sports. Players compete in series of two-player matches, and a player has to lose twice before he’s eliminated. This is done through a system of winner and loser brackets, wherein people drop from the winners’ brackets to the losers’ brackets when they lose once, and drop out altogether when they lose twice.

An improvement is the double-elimination tournament which is now one of the best known tournament systems in sports. Players compete in series of two-player matches, and a player has to lose twice before he’s eliminated. This is done through a system of winner and loser brackets, wherein people drop from the winners’ brackets to the losers’ brackets when they lose once, and drop out altogether when they lose twice.

One problem with standard double-elimination is that there are unusual situations where a significantly inferior player can still make it to the final round, or the last player to remain undefeated can lose only once and still be eliminated. These can be addressed through variants such as face-off (requiring the last two remaining competitors to compete again if the undefeated team is defeated for the first time in the finals) or by reconfiguring the loser’s brackets.

Round-robin tournaments, such as official Scrabble Tournaments involve every player playing a set number of games (24 in the 2005 World Scrabble Championship), facing opponents with similar win-lose records. They then ultimately rank players by their win-lose ratios.

Round-robin tournaments, such as official Scrabble Tournaments involve every player playing a set number of games (24 in the 2005 World Scrabble Championship), facing opponents with similar win-lose records. They then ultimately rank players by their win-lose ratios.

The advantage of these sorts of tournament over an ELO-style ranking is that they’re easily understandable and seem fair. In addition, they measure ranking in a much more topical manner: how well someone is playing during a singular instant, rather than over a longer career. As a result they work much better for a live tournament.

Different Themes: Thresholds

As we discussed in our original article on Collective Choice, thresholds are ranking barriers above which members get a special ability–or alternatively levels below which members lose a special ability. They can also act as another goal for a ranking system.

In the game of Go there are both amateur and professional players. Although they aren’t technically in the same hierarchy of rankings, the highest Go amateur ranking (7 dan) is approximately equal to the lowest Go professional ranking (1 dan), forming a de facto threshold.

In the game of Go there are both amateur and professional players. Although they aren’t technically in the same hierarchy of rankings, the highest Go amateur ranking (7 dan) is approximately equal to the lowest Go professional ranking (1 dan), forming a de facto threshold.

Likewise the United States Chess Federation uses their ELO rankings to denote Chess Masters. Anyone who achieves 2200 UCSF is given a National Master threshold ranking and anyone who maintains it for 300 games is given a Life Master threshold ranking.

Likewise the United States Chess Federation uses their ELO rankings to denote Chess Masters. Anyone who achieves 2200 UCSF is given a National Master threshold ranking and anyone who maintains it for 300 games is given a Life Master threshold ranking.

The American Contract Bridge Association uses a threshold system where you have to win a certain number of tournaments and thus earn masterpoints in order achieve official rankings such as “section master”. Furthermore, players may earn different “colors” of masterpoints depending the difficulty of the tournament, and some ranks require that you earn at least some specific colored masterpoints in order to meet the requirements for the next threshold.

The American Contract Bridge Association uses a threshold system where you have to win a certain number of tournaments and thus earn masterpoints in order achieve official rankings such as “section master”. Furthermore, players may earn different “colors” of masterpoints depending the difficulty of the tournament, and some ranks require that you earn at least some specific colored masterpoints in order to meet the requirements for the next threshold.

These thresholds are fairly explicitly based on other hierarchical ranking systems, but this doesn’t need to be the case. Since determining the purpose of a ranking system is often the first step in designing it, as we delve further into the area of thresholds we may well find that systems specifically dedicated toward measuring thresholds are more likely to do so well.

In our next article we’ll consider among other things the Avogadro reputation system, which manages thresholds in such a way as to prevent cheating.

Conclusion

There’s actually a lot of variety in ranking systems, and even though we’d like them to be totally objective, various subjective elements often creep into these systems. In addition, there’s a lot of variety in what ranking systems can do. For competitive systems, hierarchy, privilege, matching, and handicapping are some of the top purposes of ranking. Determining what a ranking system is going to do is a necessary first step in designing the system, as different systems will accomplish various goals to a better or worse degree.

ELO, in several variants, is the best studied and most used competitive ranking system. It works particularly well as a matching system. However, even ELO has flaws in it, among them: issues with new player rankings; its core two-player basis; its lack of provisions for teams; a few minor subjective elements; and problems with cheaters. New systems continue to be rolled out on the Internet to resolve these issues, and overall, it’s an area of interesting new study.

Tournament systems and threshold systems offer a few good examples of competitive ranking systems with very different purposes, underlying the need to understand what you’re doing before you do it.

Ranking systems also lay very near yet another type of Collective Choice: reputation systems. We briefly addressed reputation systems when talking about threshold systems and will return to this in our next article.

Related articles from this blog:

Related articles from Shannon Appelcline’s Trials, Triumphs & Trivialities:

Comments

A data point on ELO cheating for you: Yahoo! Games uses ELO rankings for several their two-player games. Before recent abuse mitigation changes, some people used robot to accumulate scores in excess of 6,000,000 points. The abuse-the-ranking game had become a totally seperate competition. For now, Yahoo! has capped the ELO scores at 3,000 (I think.) This removed most of the cheating incentive.

F. Randall Farmer 2006-01-05T13:46:18-07:00

In the slashdot discussion of this blog entry http://games.slashdot.org/comments.pl?sid=173988&threshold=0&mode=flat there was an interesting link to beatpaths.com, which is sort of a tourney system for when you can’t complete a full set of round-robin or double-elimination competitions, as what happens in NFL during the fall season. What is also interesting to me is that it introduces a goal for ranking systems that I’d not thought of before – prediction. The purpose of the beatpath systems is actually focused on predicting the outcome the next set of the weekend games.

Christopher Allen 2006-01-14T14:31:30-07:00

No mention of Glicko and Glicko2?

Stephen Waits 2006-01-15T08:57:38-07:00

There’s a ranking scheme that Mark Newman from the U of Michigan did for college football, which Yahoo Search turned up a pointer to here: http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20051112/mathtrek.asp quoting: Physicists Juyong Park and M.E.J. Newman aimed for a ranking system that’s fast and easily understood by fans (in contrast to the cumbersome, opaque BCS formula). They based their ranking method on the notion that, if A beats B, and B beats C, then A also beats C, even if it may not actually play C. Hence, the method counts both direct wins by beating a team and indirect wins by beating a team that beat another team. (end quote) You end up with a directed graph of teams as nodes and games as edges, and compute a function of that graph that is related to a centrality metric.

Edward Vielmetti 2006-02-02T22:18:39-07:00

This article is a great survey of the subject! I’m working on the PvP ranking system for another game with some unique problems, because the teams in a PvP match can be of disparate size and widely differing power levels, which are then balanced so that wildly mismatched teams (ignoring relative rank at PvP for the moment) are actually reasonably matched. It starts here: http://ncanson.livejournal.com/3938.html

Matthew Weigel 2008-01-31T09:55:58-07:00

Life With Alacrity

© Christopher Allen