By Christopher Allen & Shannon Appelcline [This is the second of a series of articles on collective choice, co-written by my collegue Shannon Appelcline. It will be jointly posted in Shannon’s Trials, Triumphs & Trivialities online games column at Skotos.]

In our previous article we talked about the many systems available for collective choice. There are selection systems, which are primarily centered on voting and deliberation, opinion systems, which represent how voting could occur, and finally comparison systems, which rank or rate different people or things in a simple, comparative manner.

One purpose of our previous article was to create a dictionary of terms for talking about these related, but clearly different, systems. Another was to start offering analyses of these systems, many of which had not been well studied before their introduction onto the Internet.

One purpose of our previous article was to create a dictionary of terms for talking about these related, but clearly different, systems. Another was to start offering analyses of these systems, many of which had not been well studied before their introduction onto the Internet.

However at best our previous article provided an overview of what should be further investigated in each system. This article provides more in-depth coverage of one of the systems we previously outlined: rating systems.

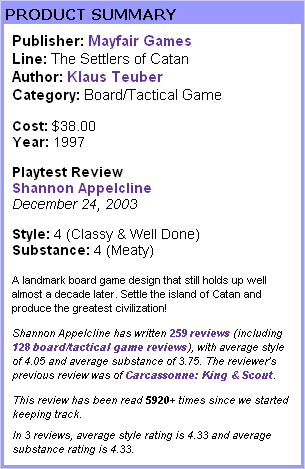

As we wrote in our previous article, in comparison rating systems “the value of individual items (most frequently goods) rise or fall based upon the largely subjective judgment of individual users.” Ratings systems should be clearly differentiated from the closely related ranking systems. Ratings systems have a more subjective component, while ranking systems are largely objective. Amazon, Netflix, BoardGameGeek, and even the Stock Market were offered up as examples of ratings systems. Another example of a comparison rating system, and one of the earliest that appeared on the modern Internet, is eBay. The techniques they use are now beginning to show their age.

eBay: A Failed Rating Experiment

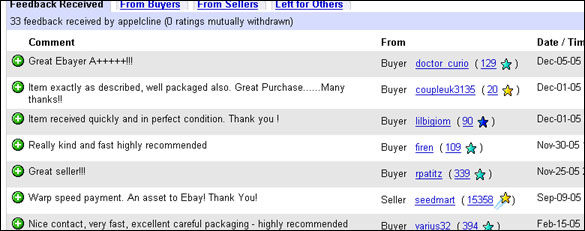

Most rating systems center around rating content, often user-contributed content, and they frequently help apply community values and acclaim to that content. However, the idea of ratings can go far beyond that narrow niche (though that will doubtless be its greatest use as the Internet continues to expand). Early Internet site, eBay, was one of the first to widely use user-submitted ratings, and it used them for a different manner: to determine the good traders on their auction site.

Most rating systems center around rating content, often user-contributed content, and they frequently help apply community values and acclaim to that content. However, the idea of ratings can go far beyond that narrow niche (though that will doubtless be its greatest use as the Internet continues to expand). Early Internet site, eBay, was one of the first to widely use user-submitted ratings, and it used them for a different manner: to determine the good traders on their auction site.

Unfortunately, as one of the first in this field, eBay made many mistakes which now leave their ratings system only slightly helpful. However, its failures can also provide us with insights in creating new rating systems on the Internet.

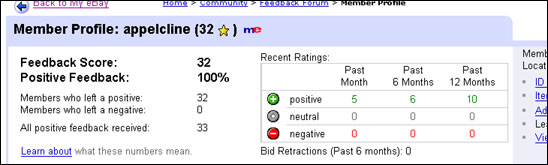

eBay allows you to leave positive, negative, or (more recently) neutral feedback for each transaction you conduct in their society. These are aggregated into two numbers. “Feedback Score” is calculated as unique positive feedback received minus unique negative feedback received, and results in a whole number like “32” or “10,302”. “Positive Feedback” is calculated as positive feedback received divided by all feedback received, and results in a percentage like “100%” or “99.8%”.

Unfortunately, for reasons discussed below, almost all feedback is positive, and thus the Feedback Score acts almost entirely as a track record of how many trades someone has made. The Feedback Score could be largely replaced by that single number. You can look at a score of “27”, and say, “That’s an amateur trader, or someone just getting started”, at a score of “3”, and say, “That person may or may not know what they’re doing”, at a score of “10,302”, and say, “That person has done a lot of trades.” But you still don’t know how good the trader is.

Theoretically, the Positive Feedback percentage should give a more meaningful number, but people so infrequently give bad ratings that, even when they do appear, they look like noise. Does a percentage of “99.8%” on a user with a score of “1,762” mean that the seller has a genuine problem or not? Do those 3 unhappy customers really represent another 30 who were unwilling to actually click the negative feedback? And, did those people have slightly bad experience or really bad experiences? It’s pretty hard to say.

Theoretically, the Positive Feedback percentage should give a more meaningful number, but people so infrequently give bad ratings that, even when they do appear, they look like noise. Does a percentage of “99.8%” on a user with a score of “1,762” mean that the seller has a genuine problem or not? Do those 3 unhappy customers really represent another 30 who were unwilling to actually click the negative feedback? And, did those people have slightly bad experience or really bad experiences? It’s pretty hard to say.

Overall, eBay has a few major problems with their rating system:

-

It’s non-granular, with only two options (positive/negative), or more recently three (positive/negative/neutral).

-

It’s non-distinct, with no useful guidelines on what behaviors should result in each rating.

-

It’s non-statistical, and thus ends up showing only a gross number of sales, not a real subjective measure.

-

It’s bilateral, with buyers and sellers rating each other simultaneously, and thus people are afraid to give bad ratings lest they get them in return.

-

It’s meaningless, because there are no good tools to control who bids on an auction based on Feedback numbers. (Technically it may be legitimate to ban low feedback bidders from an auction, then cancel their bids if they enter the auction, but this is neither obvious, automatic, nor simple.)

We’re going to address each of these issues in turn, to offer insight into creating new comparison rating systems. The first three topics–granularity, distinction, and a statistical basis–are the most important elements of a good comparison rating system. Bilateral & meaningfulness issues will only be relevant on certain sites.

(As a final caveat: in some ways eBay falls closer in ultimate result to a reputation system, a topic which we’ll be covering more in a few articles down the road, but its lessons learned are still entirely accurate for rating systems of all sorts.)

Granular Ratings

In general, people want to be nice. There are exceptions to that rule, perhaps even great numbers of them, but the average, well-adjusted person would prefer to make other people happy, not sad.

In general, people want to be nice. There are exceptions to that rule, perhaps even great numbers of them, but the average, well-adjusted person would prefer to make other people happy, not sad.

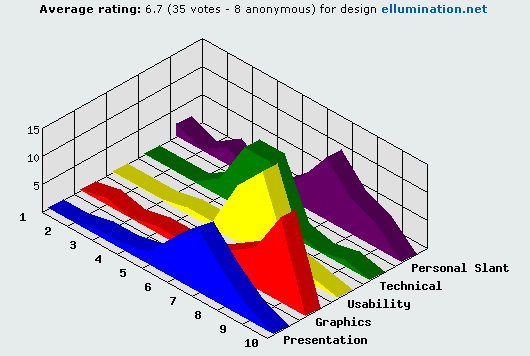

This has a notable effect on any comparison rating system, because it means that people are less likely to use the bottom half of any rating scale. If you did a statistical run on eBay, you’d certainly find that more than 99 out of every 100 ratings are positive. This is largely influenced by concerns of bilateral revenge, as discussed below, and the fact that eBay suggests other means of dispute resolution when you try and leave negative feedback. However, RPGnet, a roleplaying site which reviews games, comics, books, movies, and more shows a similar trend despite the lack of bilaterality.

RPGnet uses two 5-points scales for reviews, resulting in a total rating of 2-10. Of all the ratings at RPGnet, 6,983 reviews have a total that’s above average, a total rating of 6 or more, and 795 have a total that’s below average, a total rating of 5 or less. Perhaps there are more people who sit down to write a review because they really like a game than those who do so because they really hated it, but the result of ~90% of reviews being above average is still stunning.

The following table shows all the ratings for each of the two categories that RPGnet uses, “Style” and “Substance”:

| Rating | Style | Substance | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73 | 210 | 1.8% |

| 2 | 687 | 590 | 8.2% |

| 3 | 2127 | 1583 | 23.8% |

| 4 | 3337 | 3242 | 42.2% |

| 5 | 1554 | 2153 | 23.8% |

This evidence confirms what we’d already suspected. Only 10% of raters use the bottom two ratings in a 5-point scale, and only 2% use the bottom rating. The median of the 5-point scale is actually the fourth point, with a neat bell curve arranged around it.

Because users are innately unwilling to give bad ratings, as evidenced here, useful comparison ratings truly come about only through fractional differences between good ratings. In this case, the difference between “3”, “4”, and “5” is meaningful, and becomes more meaningful as more ratings are entered. Eventually you can look at a ranked list of ratings and see that “4.2” is a good rating while “3.5” is not.

In order to do this, however, you need enough levels of good ratings to be able to distinguish between them. eBay, only offering one positive rating, does not provide enough differentiation. RPGnet, with its three positive ratings, might. However, sites that offer a 10-point scale are the ones that really seem to be able to produce meaningful statistics. On those sites we can expect that 90% of users will choose between six different numbers, from “5” to “10”, and as the number of ratings builds up, this will produce enough differentiation to be meaningful. If you have already adopted a 5-point scale, consider allowing users to select the half-points, giving users a greater ability to differentiate their ratings.

Distinct Ratings

No two users are ever going to rate the same; different rating numbers will mean different things to each person. This can introduce minor discrepencies into ratings, if a single individual rates particularly low or high. However, because most ratings are eventually used for comparisons, if that low- or high-rater rates many different things, the ratings equalize. “Item A” is rated low by this person, but so is “Item B”, and so they end up in the correct positions in relation to each other.

A bigger problem occurs when an individual is inconsistent in his ratings over time. If an individual rates everything low for a while, then rates everything high, then he has a greater chance of biasing the overall rating pool. Worse, his individual ratings aren’t meaningful, because you can’t look at two items, see that one is a “6” and another is an “8”, and truly believe that he likes the “8” a fair amount more than the “6”. This reduces the usability of an individual recommendation system or a friends system where one user might look at what other users thought about products, because their unaggregated numbers are not accurate.

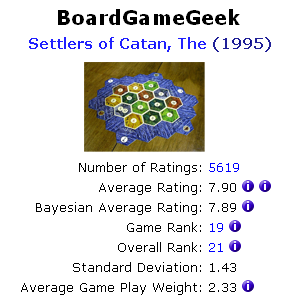

You thus want to help individuals to stay consistent, and the best way to do that is to make the criteria for your ratings distinct. BoardGameGeek, a board game web site that supports a 10-point rating system for games, does a good job of offering distinction in its ratings.

- 10 - Outstanding. Always want to play and expect this will never change.

- 9 - Excellent game. Always want to play it.

- 8 - Very good game. I like to play. Probably I’ll suggest it and will never turn down a game.

- 7 - Good game, usually willing to play.

- 6 - Ok game, some fun or challenge at least, will play sporadically if in the right mood.

- 5 - Average game, slightly boring, take it or leave it.

- 4 - Not so good, it doesn’t get me but could be talked into it on occasion.

- 3 - Likely won’t play this again although could be convinced. Bad.

- 2 - Extremely annoying game, won’t play this ever again.

- 1 - Defies description of a game. You won’t catch me dead playing this. Clearly broken.

If you offer a distinct rating listing like this, some users will still come up with their own rating ideas, but if they do, they’re more likely to remember what each number means to them. For everyone else, a very clear, s rating system is the most likely to produce meaningful and consistent results. As long as users aren’t puzzled by the distinction, they’ll be consistent in picking the same numbers for the same rating every time.

Statistical Ratings

The last big topic that you have to think about in creating most comparison rating systems is whether they’re statistically sound.

The best way to make your ratings statistically sound is with volume. If you can manage thousands or tens of thousands of ratings for each item, any anomolies are going to become noise. However, the fewer ratings you have, the more likely it is that your ratings are inaccurate in relationship to your database of ratings as a whole. (And thus one of the failures for eBay is that it tries to claim meaningfulness for users with very few ratings, where there’s clearly no statistical basis.)

Ideally what you want to do is give items with fewer ratings among your collection less weight, and those with more ratings higher weight. One simple way to do this is to apply a bayesian average. Variants of this are used by the aforementioned BoardGameGeek and by IMDB. RPGnet is using it for some unreleased software as well.

Ideally what you want to do is give items with fewer ratings among your collection less weight, and those with more ratings higher weight. One simple way to do this is to apply a bayesian average. Variants of this are used by the aforementioned BoardGameGeek and by IMDB. RPGnet is using it for some unreleased software as well.

The idea behind a bayesian average is that you normalize ratings by pushing them toward the average rating for your site, and you do that more for items with fewer ratings than those with more ratings. The basic formula looks like this:

b(r) = [ W(a) * a + W(r) * r ] / (W(a) + W(r)]

r= average rating for an item

W(r)= weight of that rating, which is the number of ratings

a= average rating for your collection

W(a)= weight of that average, which is an arbitrary number, but should be higher if you generally expect to have more ratings for your items; 100 is used here, for a database which expects many ratings per item

b(r)= new bayesian rating

Say three “shill” users had come onto your site and rated a brand new indie film a “10” because the producer asked them to. However, you use a bayesian average with a weight of 100, and thus 3 ratings won’t move the movie very far from the average site rating of 6.50:

b(r) = [100 * 6.50 + 3 * 10] / (100 + 3) b(r) = 680 / 103 b(r) = 6.60

WowWebDesigns uses a similar model and even offers a good explanation of their methods on their web site.

With everything that’s been described thus far, including granularity and distinction, a bayesian average (or some other similiar method) will probably be enough to give your ratings a good, sound statistical basis. However, sites with low volume of ratings may still be concerned with “shills” or “crappers” who come in to your site just to put “10”s on their favorite items on “1”s on their least favorite. RPGnet’s reviews are an example of a site that could experience this issue, because only a few people are going to ever write reviews for an individual item, and this small number of reviews could compromise the nature of any comparisons generated by the ratings sytems.

In short summary the following additional methods may help with this issue:

-

Rate the Raters: Reviews are low volume, but presumably readers of those reviews are high volume, and you can take advantage of that to then have your readers rate the reviews. Amazon and Netflix are two examples of sites which use this method by asking “how many readers found this helpful”.

-

Altruistic Punishment: An alternative method for rating raters is to use altruistic punishment. Herein users can punish someone who does contribute to the community, but at a cost to themselves. So, a reader could flag a poor rating or a poor review at some minor cost to their own rating. Though this method may seems somewhat paradoxical, game theory suggests that it is a generally effective technique for improving the commons.

-

Adjust Ratings Based on Ratings: Ratings can be self-adjusted based upon the rater’s own behavior. The simplest method here is to map a rater’s average rating to the average rating for a site. For example, if the average rating of a site is 6.50 and a shill’s average rating is 10.0, then those 10s should be treated as 6.50s. This has the possibility for some intensive calculations, however, and may lead to additional bias in your rating pool if shills figure out the methods you use to adjust ratings.

-

Allow Editorial Fiat: Another method is to allow editorial fiat, where editors are expected to come in and remove bad ratings (or proactively not release them). This clearly results in time issues, but they may not be major since only sites with small numbers of ratings/item will have to do this type of adjusting. Further, automated systems could flag “suspicious” rating patterns which are outside the norms for average, speed of rating, etc. (RPGnet supports editorial fiat by requiring editorial release of all reviews.)

The idea of adjusting ratings based on ratings bears a bit of additional discussion because it’s somewhat similar to another well-knowing rating system: slashdot. Herein you have both ratings and meta-ratings. People can rate threads and articles, then other people can agree or disagree with those ratings, which in turn makes it more or less likely that the original rater will be allowed to rate in the future (depending on if people agree or disagree with his ratings). Under a more general classification, this is probably a meta-rating system based on a reputation system, so it’s something we’ll look at further a couple of articles down the road.

Other Issues: Bilateralism & Usefulness

90% of the rating issues that sites will face are covered by the above. However eBay in particular raised two other issues – bilateralism and usefulness – that aren’t as generally relevant but do deserve some consideration.

Bilateralism: One of the reasons that eBay’s ratings fall apart is that they’re bilateral. Buyers and sellers rate each other simultaneously and thus there’s the fear of revenge if you rate someone badly. It’s a sufficient issue that eBay has a FAQ on the topic, though they don’t offer any good answers.

The following solution would address some issues of bilateral revenge:

-

Put a time limit on bilateral ratings

-

Release bilateral ratings simultaneously at the end of the time limit

-

Don’t allow additional ratings after the time period

This would work well on an eBay, where you’re unlikely to conclude an additional deal with someone you rated badly, and thus there’s no possibility ever for rating revenge. On a game site, however, where people are arbitrarily put into games with each other, and thus you could end up in a game with someone you rated poorly, there might be room for later revenge, down the road. This would have to be addressed to truly feel comfortable with bilateral ratings.

Additional investigation might reveal more variations of this method, or offer good answers for alternatives, like anonymous ratings.

In addition, good privacy restrictions are really needed to make bilateral ratings work, as well as Terms of Service that protect users from lawsuits for ratings. There have already been cases of physical threats based upon eBay ratings. eBay has also produced cases where people threatened slander or libel lawsuits for bad ratings, and this even further chills the possibility of true ratings appearing on the eBay server.

Usefulness: Finally, you want to make sure your ratings are useful at your sites. Rankings are a good way to achieve this. You can see the “best games ever” ranked, or you can see the most interesting user content rise to the top of a long listing, and the least interesting sink to the bottom.

eBay offers a counter example of frustration with the usefulness of ratings. As already mentioned, you can theoretically ban “bad” users from bidding on your items, and then cancel bids from these users if they appear. However, there are multiple issues with this approach. First, how do you define “bad” users on eBay? Insufficient feedback? Too much negative feedback? Too high a percentage of negative feedback? Second, there is no automated method for doing this, so you must remain ever vigilant on your auctions to make sure that “bad” users aren’t involved. Third, there’s no way to keep a bad bidder from returning after you’ve cancelled his bid. Fourth, these bad bids and cancellations have the possibility of corrupting your auction, as you could lose other bidders who came in, saw the higher bid when the bad bidder was involved, then left before the bid was reduced by his removal. Finally, greed is a powerful motivator on eBay, which might lead to the retention of bad users.

You also need to be careful with your user interface for ratings. Here is an example of a poor UI:

Conclusion

Comparison ratings are going to be an increasingly important force as the Internet continues to mature. To produce meaningful comparison ratings for your site, you need to concentrate on four important factors: granularity, specifity, sound statistics, and usefulness. And, if you offer bilateral ratings, make sure you understand the subtleties of that as well.

Related articles from this blog:

Related articles from Shannon Appelcline’s Trials, Triumphs & Trivialities:

Comments

I’ve ran into my fair share of voting systems, but by far the worst I’ve ever seen is the one used at www.animenfo.com, a database of anime products with user ratings. When giving a product a rating, a user is required to also write a constructive review on the product. However, the reviews are moderated and, often, removed from the database as “unconstructive” by the limited number of moderators. The problem with this approach is that the moderators are inevitably biased. A submitted, bad rating on a product, if reviewed by a moderator who personally likes the show being rated, is often removed from the database with the claim that the review was not constructive. Perhaps not entirely related, but an example of ratings-gone-awry, all the same. -Kalle.

Kalle 2005-12-13T10:42:58-07:00

It’s rarely used, but asking people to rank from -5 to +5 can be better than ranking from 0 to 10. You make it very clear that “0” means average/neutral. You won’t entirely eliminate the positive bias in ratings but you can reduce it. And you bring everybody closer to the same mean. I’ve concluded over time that in fact the response to a negative feedback on eBay should be disabled, as it contains no information. Who, after all, is going to give a positive feedback to somebody after they have slapped a negative on you? The likely choices there are no-feedback or neutral from a charitable person and of course a revenge negative. So they could make it simpler. If the first person gives a negative, the transaction is considered sour. In your stats it would list the number of first-negatives you left for others. (The number of negs you leave for others is already visible but harder to find.) Ideally split buyer/seller.

Brad Templeton 2005-12-13T13:11:31-07:00

An interesting point missing from this good summary: Many huge ratings sites see a clear bimodal distribution of scores when rating products(movies, cds, books, etc.) with a simple scoring scheme, such as a single 5-star scale: The nodes are at 1 and 5 stars, with the love-or-hate scores making up more than 80% of all scores. Clearly, some of that is a function of the intrinsic cost vs. incentive structures of completing ratings and reviews. When there is a clear direct benifit to the user (such as Netflix, Slashdot, or Yahoo! Music’s Launchcast) ratings tend to distribute a bit more evenly (but just a bit.) My point is that the actual end-user application of the rating has a large effect on the nature of the scores that will be created.

F. Randall Farmer 2005-12-14T16:13:25-07:00

I find when people give a bad rating on anything from eBay to those hotel and restaurant review sites its usually as a result of an extremely negative personal experience therefore the rating tends to be exagerated and totally not objective. A blind system like the porposed solution to eBay bilateralism issue is probably best. I’ve been a mystery shopper for a handful of restaurants and the system works quite well. In this system the purpose is to behave exactly like a regular consumer. You sit down, ask about the specials, take mental note of everything from the bathroom sink to the temperature of the food (and a hundred other details), but you don’t behave in any way that would alter the staff you are a mystery shopper (for example writing things down is strickly prohibited). Upon returning home you complete a lengthy questionnare about all the details you were supposed to notice. In this system the rewards is for a thorough assesment, regardless of its positive or negative slant. The more detail you provide the better assignments you get next time around. Even if you totally slam a place, but you provide substantial detail, you will be “promoted” to a “bar visit” or something much more rewarding than the typical lunch visit. So, I also agree with this articles suggestion to rate the raters, akin to what Amazon does but without the bias towards volume. I would also addd that there is no middle ground on such ratings. Whether the choices range from Strongly Agree to Strongly Dissagree, or from “shortest wait” to “longest wait” there is no ‘neutral’ choice, nothing is “just right” as in the story about the three bears and the porridge. Even with numerical choices they are always even, not odd, so there is not chance of ranking in the middle. I like that. I think it pushes you to be more realistic. Having a middle ground leaves the undecided the opportunity to not make a decision. A “middle” rating is of no use to anyone.

Shally 2005-12-21T16:23:26-07:00

Researcher Paul Resnick has been looking at eBay, too. His blog is at http://www.livejournal.com/users/presnick/ and has posts like eBay Live Trip Report: http://www.livejournal.com/users/presnick/8121.html There are a few relevant articles as well, at http://www.si.umich.edu/~presnick/#publications

Seb 2005-12-29T05:53:29-07:00

Good work there, and very thorough. Can we distinguish the social/transactional from the object/informational aspects of a rating situation? I’m just wondering aloud. On the one hand is the fact that publishing one’s rating of a transaction will reflect on the transaction partner, on oneself, and so is social. On the other hand is the fact one can indeed rate an experience with some objectivity, assuming that the soft stuff has been bracketed out. I dont see how we can bracket out the social though, at least in a way that users will be able to participate in. There’s a thing about sincerity as a type of interaction: it’s an attribute of expression that cannot be stated explicitly (say that you’re being sincere and you throw your sincerity into quesion immediately). Ratings may fall into that kind of category of linguistic and metalinguistic acts..

adrian Chan 2006-01-04T09:47:53-07:00

URL: Wow, thorough and cogent. Of all of the points, one missed opportunity occured to me while reading, and that is on the EBay statistical validity criticism. The phrase ‘thus one of the failures for eBay is that it tries to claim meaningfulness for users with very few ratings, where there’s clearly no statistical basis’ struck me as off. Human transactions are not mechanical actions - they involve situations that often matter. Hence a particular negative may really be cause for serious concern, even if there are not yet many ratings. Also, beginners are not inherantly less important than experienced traders. So though difficult, credit, or blame, is rightly awarded even on the basis of just a few transactions. Exactly how is a subject of further refinement. I have read some of the EBay dissection papers a while back. This post is far more comprehensive, that is wide ranging, and yet not missing clarity, accuracy or nuance. Master work.

Brian Hamlin 2006-05-30T00:43:49-07:00

I have an interesting brainstorm for you about the netflix challenge: http://www.thinksketchdesign.com/2008/05/03/design/coding/does-the-netflix-challenge-have-it-backwards cheers - thinksketch

thinksketch 2009-03-03T18:56:13-07:00

Life With Alacrity

© Christopher Allen