In my first article in this series I talked about community numbers: how the sizes of groups ultimately affect their success (or failure). However what I discussed only offers up the most rudimentary explanation of the dynamics, and that is because typically not all of the members of a group are equally involved.

In order to better define who constitutes the tightly-knit “participant community” upon which the group thresholds act, we have to study power laws which let us measure the intensity of individuals’ involvement in a group.

An Overview of Power Laws

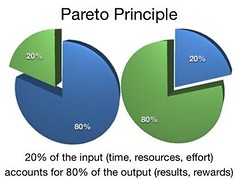

The best-known power law is probably the Pareto principle, which is otherwise known as the “80/20 law.” It’s been overused throughout the years; Pareto’s actual law only said that 80% of the wealth would be held by 20% of the population.

However, it offers a fine example of how power laws work. They generally describe a discrepancy between intensity and population: inevitably, some people do a lot more of the work in any social situation. Other examples include Zipf’s Law, which suggests that the frequency of a word’s usage is

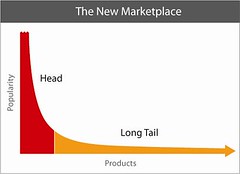

inversely proportionate to its ranking among words (making the second ranked word appear half as much, the third a quarter as much, etc), and the long tail, which talks about selling a very large number of it

ems in a very small individual quantity.

inversely proportionate to its ranking among words (making the second ranked word appear half as much, the third a quarter as much, etc), and the long tail, which talks about selling a very large number of it

ems in a very small individual quantity.

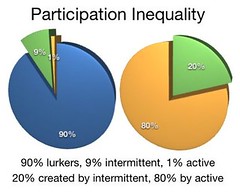

For online communities, which have been the focus of most of my studies on the topic of community sizes, I’ve found that the participation inequality power rule is very apt.

Participation Inequality

This term comes from Will Hill of AT&T Laboratories, who said, “A major reason why user-contributed content rarely turns into a true community is that all aspects of Internet use are characterized by severe participation inequality.” It’s often equated with the 1% law, though I like to be more precise and say that 90% of an online community tends to be lurkers, 9% tends to be intermittent participants, and 1% tends to be active participants.

This term comes from Will Hill of AT&T Laboratories, who said, “A major reason why user-contributed content rarely turns into a true community is that all aspects of Internet use are characterized by severe participation inequality.” It’s often equated with the 1% law, though I like to be more precise and say that 90% of an online community tends to be lurkers, 9% tends to be intermittent participants, and 1% tends to be active participants.

These values heavily influence online community sizes that are larger than the tightly-knit communities group thresholds that I previously discussed.

Power Laws & Group Thresholds

When I wrote about tightly-knit communities in my first article, I didn’t consider the degree of participation. That’s certainly an entirely valid model for some types of groups. Corporations, for example, ideally should be entirely filled with active participants, while Skotos’ online game Castle Marrach also fits into the category due to the implicit requirements it creates for participation. There are some challenges to grow this type of community, since you’re only searching for a specific type of high-energy participant — but they can be overcome if you offer sufficient incentive (such as a salary or a lot of internal feedback).

However, most communities, and in particular, online communities, will not fall into this category, and thus when we’re looking at group thresholds, we have to measure them against the number of active participants, not against the number of total members. Thus, for groups which allow for non-participation, we’ll often measure 10% (or maybe 1%) of the group size against the group thresholds.

RPGnet, one of the community sites that Skotos runs, offers a good example of this. We regularly see monthly uniques of approximately 200,000 users. However we probably have about 20,000 active registered users, confirming the lurker:participant ratio. When we recognize that only 2,000 of those are particularly active participants and that they’re divided upon 6 successful forums, we start to see how community numbers that actually match the group thresholds can gel.

You can reverse this approach and look at active participants first. During some recent consulting for a local non-profit organization with 60 active online members, I was able to infer that their broader community was around 6000, which turned out to fairly accurately predict the total number of people who came to their live events over the course of a year.

Generally, this logic can be applied to a community of any size. You first measure whether it’s an all-participant community or one that matches an existing power law, and then you use the corrected community number to truly measure which of the group thresholds may apply to it.

Power Laws & Leaders

The power laws can also help you to measure the number of leaders in a community. Inevitably all of your participants will become leaders of some sort, while your high-level participants will become the top-tier leaders.

I noted this in my first discussions of group threshold. In a group of 7 members, you can reasonably expect to have one higher level participant, and thus the one leader that we saw naturally appear. Similarly in a Judas group of 13, there’s the opportunity for more than one leader to appear, creating the possibility for the first hierarchical conflicts.

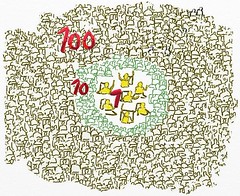

Understanding your count of leaders can help you see how to grow groups. For example when I first created iPhoneWebDev I had to do an immense amount of effort to grow the community. This is because with Participation Inequality I had to grow the group by 10 members before I got the least amount of help increasing the content of the group and I had to grow it by 100 members before I had someone who was doing as much work as I was to create content.

At 100 members, with my first active participant, we continued to grow, but we were both were working hard and felt rather lonely.

I finally saw the group stabilize, then take off on its own, when it hit 600-700 members, and that shows how beautifully the power logs work hand-in-hand with the group thresholds. With 700 members, I could reasonably expect there to be 7 leaders. In other words, I had a committee of leaders: the perfect size for a starting working group.

I finally saw the group stabilize, then take off on its own, when it hit 600-700 members, and that shows how beautifully the power logs work hand-in-hand with the group thresholds. With 700 members, I could reasonably expect there to be 7 leaders. In other words, I had a committee of leaders: the perfect size for a starting working group.

From my experience with other online groups, if the iPhoneWebDev grows to over 10,000 members, I can expect that there will be some transition issues. As the core active community members exceed 100 people I will start having some Non-Exclusive Dunbar Number problems, typically social contract failures. These can be solved by either adding some hierarchy (appointing some people to be official “staff”), or by starting to break the group into sub-communities.

Varying the Power Laws

In my first article, I noted that it’s possible to expend additional energy to make tightly-knit groups able to function effectively at non-optimal sizes. It is similarly possible for the values of the participation inequality sized groups to change by expending more energy. Conversely, a drain on energy may decrease this ratio.

For example when I used to run AOL forums I would frequently reward first-time participants with free time (at that time worth $5 an hour) if they asked good questions or offered valuable input. CompuServe similarly offered constructive feedback by telling users how many responses they’d received to a new comment when they logged back in, encouraging them to leave lurker status. More energy in the community — driven either by the moderators, good social software design, or by a greater commitment by its members — can allow you to increase the active participant percentage, maybe times 2, or even 4, but even with a lot of effort not by an order of magnitude.

For example when I used to run AOL forums I would frequently reward first-time participants with free time (at that time worth $5 an hour) if they asked good questions or offered valuable input. CompuServe similarly offered constructive feedback by telling users how many responses they’d received to a new comment when they logged back in, encouraging them to leave lurker status. More energy in the community — driven either by the moderators, good social software design, or by a greater commitment by its members — can allow you to increase the active participant percentage, maybe times 2, or even 4, but even with a lot of effort not by an order of magnitude.

As a group grows in size, I believe the participation inequality worsens. A huge Yahoo! group with a million members might have moved from a 90/9/1 ratio to 95/4.5/.5. I suspect this is because the energy required to change the participation inequality numbers is so large as to not be economical.

There are also some interesting interrelations between the numbers of people at the various levels of participation. Though discovering 100 new members has a good chance of adding 10 new participants, 1 of whom is very active, my experience has been that things trickle-down in the other direction as well: that adding 1 new high-level participant can lead to the creation of 9 medium-level participants and 90 lurkers (though don’t let that suggest that all of your effort should be expended on the high-level participants only).

Looking at Participation Inequality

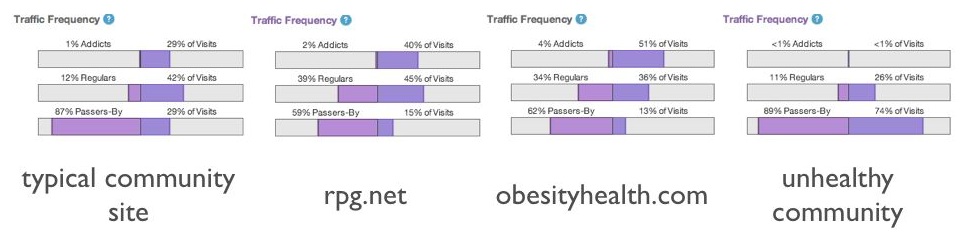

Here is a close look at four online communities, using the quantcast.com metrics service, where you can see some participation inequality in action:

From this you can see a typical online community site shows the normal 90% 9% 1% participation inequality. RPGnet shows a slightly better then average participation inequality due to its longevity and the quality of the community. ObesityHealth shows evidence of a great community with its 4% active participants, probably because you have to be very committed if you are going to have bariatric surgery. Last, an example of relatively unhealthy community that is unable to sustain its active participants.

You do have to be careful when analyzing quantcast numbers if you see active participants of greater then 6% — in almost all cases if you look deeper it is because there is some restriction that keeps people from lurking, either a fee or some other type of gateway, causing a distortion in the statistics.

Conclusion

Multiple factors influence the success (or failure) or community. As we saw in my first article on community numbers, the first factor is the differing group thresholds of community sizes. In my second article, I show that personal limits on the number of people you can have intimacy and trust with is an important factor. In this article I show that larger groups are subject to the power law of participation inequality, causing a small fraction of a community to be subject to group thresholds. In all three articles I show how expending energy can allow you to change the numbers, but with limits.

I hope this discussion of community numbers will give you some tools to look at the communities you are in, or are trying to build, and to better understand how to make them more successful.

Some other posts about the Dunbar Number and group size issues:

- 2004-03: The Dunbar Number as a Limit to Group Sizes

(also some really good comments)- 2005-02: Dunbar Triage: Too Many Connections

- 2005-03: Dunbar, Altruistic Punishment, and Meta-Moderation

- 2005-07: Cheers: Belongingness and Para-Social Relationships

- 2005-08: Dunbar & World of Warcraft

- 2005-10: Dunbar Number & Group Cohesion

- 2008-09: Community by the Numbers, Part One: Group Thresholds

- 2008-11: Community by the Numbers, Part II: Personal Circles

My bookmarks to various papers and websites on this topic are available at delicious.com/ChristopherA under some of the following tags:

- participation inequality - more specifics on participation inequality.

- participation inequality - everything I have on the topic of power laws, including participation inequality.

If you have any links on this topic that you would like to share with me, tag them for:ChristopherA and I’ll take a look.

Illustrations by Nancy Margulies. Many thanks to Shannon Appecline and F. Randall Farmer for their assistance with this series.

Comments

Having been the leader in several groups, I can truly relate to Participation Inequality. Wow, it’s tiring being the driving force behind a tremendous idea until it takes off.

Barbara Ling, Virtual Coach 2009-03-20T02:34:32-07:00

It has been interesting to be part of a local blogging community and how it actually somewhat detracted from my overall bigger online community I was a part of before. I seemed to have kept only the most dedicated readers (1%) from just simply joining a local group.

logtar 2009-05-18T11:49:00-07:00

Chris - this was a really great series of 3 posts - it is outlined as well as anything I’ve seen on the subject. In the course of your experience have you seen much of a difference between the style of content produced in communities and how that impacts the power law? A few years ago I started a project to create an open source methodology for information management http://www.openmethodology.org, which worked in concert with corporate solutions also built in a collaborative fashion. At least in this case, we have found the power law threshold to be even higher when creating a more structured, method-based approach to collaboration. We did feel there was a need to put some controls in place for an “open method” and have experimented with different ways to build a collaborative commmunity. Some good progress has been made, but its been tough going! We also applied this same approach to sustainability http://www.open-sustainability.org. Once again, very hard work to build the community but some slow steps are being made. Do you have any thoughts around more structured collaboration and how it can negatively impact community growth in readership and contributions? Any recommendations on ways to improve it?

Sean McClowry 2009-07-15T15:33:05-07:00

Life With Alacrity

© Christopher Allen