Lately I’ve been noticing the spread of a meme regarding “Dunbar’s Number” of 150 that I believe is misunderstanding of his ideas.

The Science of Dunbar’s Number

Dunbar is an anthropologist at the University College of London, who wrote a paper on Co-Evolution Of Neocortex Size, Group Size And Language In Humans where he hypothesizes:

… there is a cognitive limit to the number of individuals with whom any one person can maintain stable relationships, that this limit is a direct function of relative neocortex size, and that this in turn limits group size … the limit imposed by neocortical processing capacity is simply on the number of individuals with whom a stable inter-personal relationship can be maintained.

Dunbar supports this hypothesis through studies by a number of field anthropologists. These studies measure the group size of a variety of different primates; Dunbar then correlate those group sizes to the brain sizes of the primates to produce a mathematical formula for how the two correspond. Using his formula, which is based on 36 primates, he predicts that 147.8 is the “mean group size” for humans, which matches census data on various village and tribe sizes in many cultures. The following chart shows the distribution produced by Dunbar’s analysis:

This number of 150 has become “Dunbar’s Number” and has been popularized by various very popular business books such as Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (summary), Duncan J. Watts’ Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age (review) and Small Worlds: The Dynamics of Networks between Order and Randomness (review), and Mark Buchanan’s Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Science of Networks (review), the ideas from which are the foundation of the various Social Network Services that I’ve discussed elsewhere in this blog.

Revisiting Dunbar’s Number

Lately, Dunbar’s number has been taken as a mean size for online networks and groups, as shown in Ross Mayfield’s Weblog, where he states:

Network Size Description Distribution Political Network ~1000s Blogs as mass media Power-law (scale-free) Social Network ~150 Blogging Classic Bell-curve (random) Creative Network ~12 Blogs as dinner conversation Dense (equal)

However, Dunbar’s work itself suggests that a community size of 150 will not be a mean for a community unless it is highly incentivized to remain together. We can see hints of this in Dunbar’s description of the number and what it means:

The group size predicted for modern humans by equation (1) would require as much as 42% of the total time budget to be devoted to social grooming.

…

My suggestion, then, is that language evolved as a “cheap” form of social grooming, so enabling the ancestral humans to maintain the cohesion of the unusually large groups demanded by the particular conditions they faced at the time.

Dunbar’s theory is that this 42% number would be true for humans if humans had not invented language, a “cheap” form of social grooming. However, it does show that for a group to sustain itself at the size of 150, significantly more effort must be spent on the core socialization which is necessary to keep the group functioning. Some organizations will have sufficient incentive to maintain this high level of required socialization. In fact the traditional villages and historical military troop sizes that Dunbar analyzed are probably the best examples of such an incentive, since they were built upon the raw need for survival. However, this is a tremendous amount of effort for a group if it’s trying not just to maintain cohesion, but also to get something done.

Furthermore, Dunbar specifically restricts himself to physically close groups:

… we might expect the upper limit on group size to depend on the degree of social dispersal. In dispersed societies, individuals will meet less often and will thus be less familiar with each, so group sizes should be smaller in consequence.

My anecdotal evidence generally seems to support the idea that group sizes will usually plateau at a number lower than 150 participants. This comes from 20 years of doing facilitation both on and offline, running several software companies, and running various forums at America Online. In particular, many online communities provide good evidence for Dunbar’s Number actually being an upper limit (either due to reduced efficiency or due to increased dispersion).

Dunbar & Online Communities

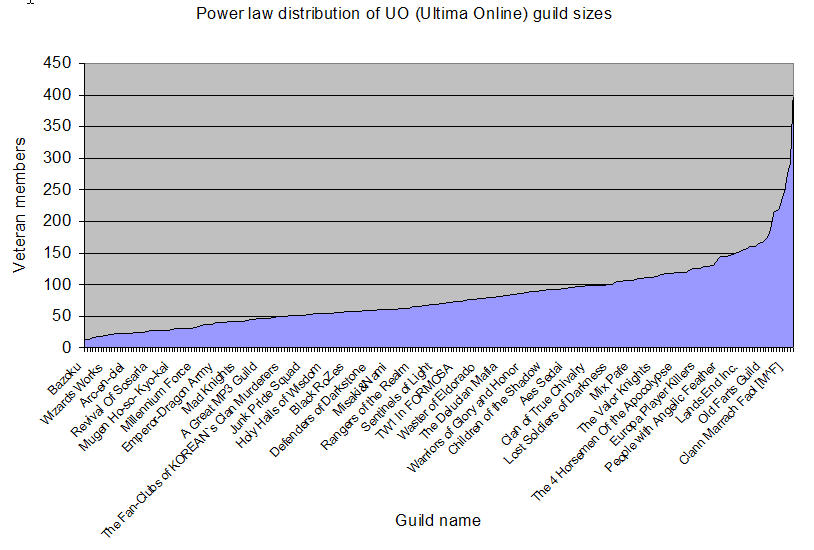

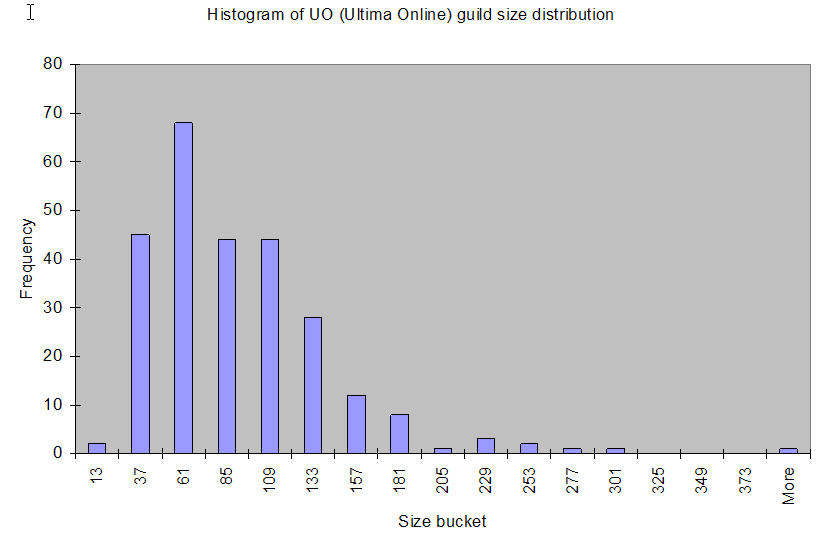

Ultima Online provides one of the best examples of what sizes an online community will support because it’s well documented and the overall game size is large enough to generate many smaller communities. If you look at Raph Koster’s statistics for the size of groups in Ultima Online, you will see a definite point of diminishing returns at around 150; however, you will also see that most groups are around 60 large.

Jessica Mulligan, executive producer at Turbine Games, confirmed these numbers to me:

The numbers match up with my (currently) mostly anecdotal evidence for Asheron’s Call. We have allegiances in the hundreds and even thousands of members, but most of those members are inactive, non-participatory in the group on a regular basis or are mule accounts for farming XP. It is rare to have more than 40 or so active participants in an Allegiance.

I’ve seen similar limits myself in some of the small online games that Skotos produces. For instance, in Castle Marrach, which is a social-dominant game (i.e. like a MUSH), the game grew quickly until we reached approximately 150-200 active users. However, whenever it grew beyond that number, it always seemed that politics and dissatisfaction would bubble up such that people would drop out, leaving us back close to 150 or 160. (That we would ever exceed 150 is a bit of a surprise, but I think it’s due to any number of factors, including a variable 24-hour user base, wherein on a given day we might only see a little more then half of our community members, below Dunbar’s Number, and only get up to close to 200 or so over a full week.)

We have had some games at Skotos that do manage to overcome Dunbarrian social limits, prime among them The Eternal City which regularly exceeds the Marrach community by more then double. However, TEC is a much more achievement-oriented game, meaning that people spend much of their time interacting with the environment – fighting monsters and training skills as it happens – rather than directly interacting with other players all the time. Thus social limits become less important.

Other online communities that I’ve had experience with have been more traditional, and thus more closely met my expectations for Dunbar’s Number acting as a limit rather than a mean. When I managed the Mac Developer’s Forum community on AOL, a forum would start to break down when it reached about 80 active contributors, requiring a forum split before continued growth could occur. Wikis provide another good example; the WikiPedia, one of the largest active Wikis online, appears to have hovered at approximately 150-175 active administrators for over a year, in spite of a huge growth in usage during the same period.

These numbers just keep coming up.

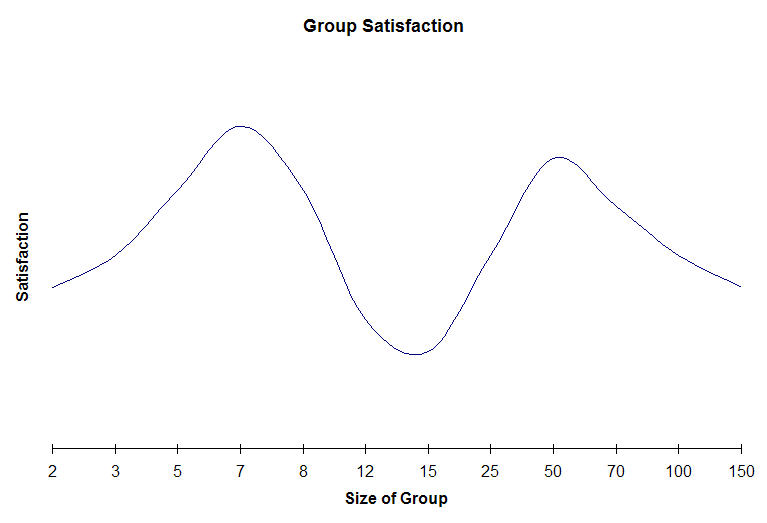

This all leads me to hypothesize that the optimal size for active group members for creative and technical groups – as opposed to exclusively survival-oriented groups, such as villages – hovers somewhere between 25-80, but is best around 45-50. Anything more than this and the group has to spend too much time “grooming” to keep group cohesion, rather then focusing on why the people want to spend the effort on that group in the first place – say to deliver a software product, learn a technology, promote a meme, or have fun playing a game. Anything less than this and you risk losing critical mass because you don’t have requisite variety.

Thus Dana Boyd gets it right when she uses the word MAXIMUM in her eTech Talk, not average or mean:

[Dunbar] found that the MAXIMUM number of people that a person could keep up with socially at any given time, gossip maintenance, was 150. This doesn’t mean that people don’t have 150 people in their social network, but that they only keep tabs on 150 people max at any given point.

Expanding Dunbar’s Numbers

To open up the discussion a bit, I’d also hypothesize that Dunbar’s Number is just one datapoint in an overall equation describing what group sizes work and what don’t. Working our way up from the smallest group sizes, I think we can find many break points, both above and below Dunbar’s Number of 150.

In my experience the smallest viable group size seems to be somewhere in the range of 5 to 9.

Looking smaller, we see that a group of 2 can be tremendously creative (ask any parent), but often has insufficient resources and thus requires deep commitment by both parties. Notably, often the difficulty of a 2-person business partnership is compared to that of a marriage. A group of 3 is often unstable, with one person feeling left out, or else one person controlling the others by being the “split” vote. A group of 4 often devolves into two pairs.

In my opinion it is at 5 that the feeling of “team” really starts. At 5 to 8 people, you can have a meeting where everyone can speak out about what the entire group is doing, and everyone feels highly empowered. However, at 9 to 12 people this begins to break down – not enough “attention” is given to everyone and meetings risk becoming either too noisy, too boring, too long, or some combination thereof. Although I’ve been unable to find the source, I’ve heard of some references to a study from the 1950s that says that the optimum size for a committee is 7. Likewise, it’s fairly easy for us to see and agree that a dinner party starts to break down somewhere above 7 or 8 people, as do also tabletop games of both the strategic (I prefer 5) and role-playing varieties (I prefer 7). These size limits can be overcome, but require increased amounts of “grooming”.

The chasm that starts somewhere between 9 to 12 people can be especially daunting for a small business. As you grow past 12 or so employees, you must start specializing and having departments and direct reports; however, you are not quite large enough for this to be efficient, and thus much employee time that you put toward management tasks is wasted. Only as you approach and pass 25 people does having simple departments and managers begin to work again, as it starts to really make sense for department heads to spend significant time just communicating and coordinating (and as individual departments become large enough to once again allow for the dynamic exchange of ideas that had previously occurred in the original 5-9 member seed group).

I’ve already noted the next chasm when you go beyond 80 people, which I think is the point that Dunbar’s Number actually marks for a non-survival oriented group. Even at this lower point, the noise level created by required socialization becomes an issue, and filtering becomes essential. As you approach 150 this begins to be unmanageable. Once a company grows past 200 you are really starting to need middle-management, but often you can’t afford it yet. Only when you get up past that, maybe at 350-500 people, does middle-management start really working, primarily because you’ve once again segmented your original departments, possibly again reducing them to Dunbar-sized groups.

The following chart shows anecdotal satisfaction ratings for these lower group sizes:

Much of this is probably predicted by Dunbar’s model, if you add in the non-survival and dispursed community modifiers that I discuss here. Essentially, as we increase group sizes beyond 80, to 150, 200, or even 350-500, we typically do so by breaking larger groups down into smaller ones, and continually reducing community sizes down to the point where they can be understood and managed by people – and so efficiency reasserts itself.

Since this post was originally posted, I have added a number of other posts about the Dunbar Number and group size issues:

Comments

Excellent analysis!!! We must remember that people in a group are connected by direct AND indirect ties. We can keep tabs on many via indirect ties.

Valdis 2004-03-10T14:55:59-07:00

Chris, this is a very impressive and useful piece of thinking - quite a contribution. The formulation ‘7 plus or minus 2’, which I have often heard (and used) over the years as an ideal team size is well-supported by your thinking. It’s worth noting that team-size in thriving real-world team games (basketball, baseball, US football) hover in this area.

Tom 2004-03-10T15:19:21-07:00

Chris, Pretty amazing stuff. I’d like to add another break-point. It is anecdotal (but amazingly consistent based on my experience.) I was part of a company that grew very quickly both organically and through acquisition. In every single office, things worked as you stated from 5-8(or 9), broke down until about 25 and then stabilized. However, the next breaking point was consistently between 50 & 60. It became my theory after witnessing this again and again that at around 40 people, the *PHYSICAL SPACE” requirements become so large, that you can’t easily shout across them. This may sound silly, but what that physical separation creates is a dynamic where decisions are made on “one side” without the “other side” being involved. Up to this point most everyone feels included in the whole because news travels so fast, and is often within earshot. Once we passed 40, the only news that travels fast is bad news and “secrets.” ;-) After much trial and error in trying to scale up offices with “teams areas” of multi-disciplinary folks, we ended up creating physical pods which accomodated 25-35 people. This allowed enough people to manage and have economies of scale, but small enough for quick communications. The 80 breaking point is certainly when the next breakdown began in those offices that grew that big, but it wasn’t until we got closer to 100 that the crap really hit the fan. Hope this adds to the discussion and again… wow on the piece.

Kyle Shannon 2004-03-10T16:12:45-07:00

Nice job. FYI, we have intentionally segmented the forums on SWG and other games in order to reduce the admin load–this also entailed getting rid of the “general” forum, because it served as an attractor for too many people. Smaller communities of interest prove to be far more manageable from a policing point of view because of peer pressure and tighter social strictures.

Raph 2004-03-10T16:20:22-07:00

URL: Interesting stuff. But, what is a “group”? If it means ‘the number of individuals with whom any one person can maintain stable relationships’, the what is “stable” and what is a “relationship”? What is the context of relatedness? Is the point of orientation a conversation? a product? a service? an battle? a political action committee?

Rob Kost 2004-03-10T17:47:30-07:00

Well put, its important people understand the scaling limits at 12 and 150. I never ventured a guess at optimal group size, as its heavily context dependent. Instead I would suggest that our challenge as creators of social software is to enhance social capital so productive teams can be dynamic while extending their limits with cohesion. On 12 & 150 with Wikipedia: http://ross.typepad.com/blog/2004/01/phantom_authori.html

Ross Mayfield 2004-03-10T19:59:58-07:00

Great article & comment thread, Christopher – thanks for posting that. Was there something in particular that prompted you to write this? Love to hear the backstory if there is one.

AJ Kim 2004-03-10T20:46:19-07:00

Great stuff, Christopher! I like to include the following in explanations of the 147.8 number, because the range is pretty large (100 to 231): “Because the equation is log-transformed and we are extrapolating well beyond the range of neocortex ratios on which it is based, the 95% confidence limits around this prediction (from formulae given by Rayner 1985) are moderately wide (100.2-231.1).” From Dunbar’s 1993 Behavioral and Brain Sciences article.

Peter Kaminski 2004-03-10T23:19:39-07:00

Interesting. I just finished an analysis of the e-learning industry here in New Brunswick, Canada. of the 40+ companies surveyed, almost all of them were less than 8 or more than 50 employees. Nobody in the middle, as it seems that’s an uncomfortable place to be. Also, I remember reading about W.L Gore Assoc, who insisted that all of their plants have less 150 people. More than that and they would create another plant, even if it was next door. Something about group cohesiveness.

Harold Jarche 2004-03-11T08:15:17-07:00

URL: The references to Ultima Online parallel my experiences with the game. Most guilds that I socialized with or had battles with showed the most solidarity with only 5 to 8 players present in the same area. With too many players, things would get ‘silly’ as players would become bored. Also, too many players in a guild would cause fragmentation since players could never be on at the same times or preferred to play in a different part of the world. When I played, the largest guild around was HKU (Hong Kong Union) with 230+ members. It was a common occurrence to spot two HKU members fighting in anger. I have no idea how the guildmaster of HKU managed to get any actual game play in. :) Excellent article Chris!

Wes Connell 2004-03-11T09:48:00-07:00

Just wanted to add my agreement. The larger the general communities get, the weaker the signal in any discussion. I think barriers to globally-broadcast participation can alleviate that to some extent. For instance, we charge some in-game currency (gold) to post on the in-game general forums. We’re even considering charging gold to file a complaint against another player, as the validity (signal) of people’s complaints (communication) against others has also declined as the population as gotten larger. –matt

Matt Mihaly 2004-03-13T11:40:08-07:00

Chris, Must be tough keeping up with all the compliments :-). Let me add mine but also point back to Raph’s comment earlier. The most amorphous piece here is the defintion of a group. I would also suggest that as opposed to non-human primates, humans have the ability to segment their neocortical capacities discretely between various groups and for various function - they can change roles completely. Thus we have multiple networks layered on top of each other - some w/ 2 members, some with 1000 and we swap our focus among them depending on our task, goal, etc. I think that Dunbar’s number is a strong predictor of a single group’s optimal size but not so much of an individual’s capacity to maintain multiple social contexts.

mark oehlert 2004-03-15T06:29:47-07:00

Although I haven’t read Dunbar’s work directly, the material I have read suggests that individuals are keeping track of “who did what to whom”, suggesting that group complexity grows as n^2. When n=40, we’re well within our limits, and we can handle many groups of such size (and we all have multiple social groups). My theory is that when n=150 or greater, we’re pushing the boundary, and our ability to handle multiple social groups is diminished. Marvin Harris, noted anthropologist, says in his book “Our Kind” (isbn:0060919906) that you can find no cases of larger groups forming except when there is both direct military power and no place to else to go. Let me reemphasize this: In no case in history can we find groups that voluntarily formed that were significantly larger than Dunbar’s number. Larger groups formed only when agricultural communities created food, that food was controlled by a chief who had armed guards/police, and it was impossible to splinter off into a new tribe because there was no other life-sustainining land to go to. – Will

Will Hertling 2004-03-15T18:42:02-07:00

URL: Anthopological research shows that primate groups thirve at about the size of 30 members. Human tribes in traditional tribal communities around the world demonstrate that same ideal number. Here’s a thought: If you we could manage group relationship the way of some sports leagues, we would maintain A, B, C… Groups. We would work with each of these groups differently and communicate in different ways. Individuals could move up and down as their relevance to our current activity changes. You know come to think of it… I think I already do group people like that! The A’s are the ones I meet with in person at least once in a while. The B’s are the ones I call at least somewhat frequently and the C’s are the ones I email with. I guess there’s a group that could be an A+ which are people who have directly lead me to business or are current customers. That would be a very short list, but the most protected and fruitfull. In that paradigm, these tools are helping me turn C’s into B’s and A’s, and helping me grow my C farm. The more C’s I have which can be turned into B’s and A’s, the better my networking results!

Shally 2004-03-15T18:43:12-07:00

URL: Dunbar would agree with your main point: “… the suggestion [in his paper] is simply that there is an upper limit on the size of groups that can be maintained by direct personal contact. This limit reflects demands made on the ancestral human populations at some point in their past history. Once neocortex size has evolved, other factors may of course dictate the need for smaller groups. Precisely this effect seems to occur in gibbons and orang utans: in both cases, neocortex size predicts groups substantially larger than those observed for these species, but ecological factors apparently dictate smaller groups.”

Rick Thomas 2004-03-15T19:08:58-07:00

URL: I’ve never seen this stuff before but it jibes really well with a hypothesis I had made, based on personal observation of group dynamics in my local pagan community, particularly the coven(s) with which I have worshipped the last seven years. The points at which the dynamics change seem to hover around powers of two: one person, two people, three or four people, five to eight, etc. While thirteen is a traditional “target” the groups I’ve circled with have ranged in membership from three to thirty. In my observation, when a group fell below five active members for more than a few weeks it either sought out new students, merged with another small group, or dissolved completely. Groups ranging from five to ten members tended to be most stable, with all members actively participating under the “leadership core” of two to four persons. Groups of nine to fifteen people tended to split into “active” and “less-active” members with the active component having five to nine participants. This commonly led to less active members either dropping out entirely (reducing overall group size) or complaning mightily about being left out. The one group which grew above fifteen participants, reaching thirty at its maximum, was extremely unstable as the leadership core struggled to coordinate three sub-groups, each of whom complained mightily about lacking the leaders’ attention and feeling left out… It seems that the 16-32 person group is the one that really needs a leader, though leadership develops at the 9-15 level. Would be interested in seeing if someone has applied this direction of thought (Dunbar’s number, etc) to decision-making processes in groups. A group that can’t make a decision can’t (as a whole) do much of anything else, either.

Thena 2004-03-16T20:29:35-07:00

Sébastien Paquet had a comment in his blog http://radio.weblogs.com/0110772/ I thought was interesting: “Note that if this graph is accurate, jury duty (size=12) must be pretty nerve-wracking!)” I hadn’t even thought of jury duty as an example, and I just recently was foreman of one. With only one example my experience is purely anecdotal, but I think the value of 12 in a jury is that that the group isn’t cohesive, and has a tendency to break into two groups, i.e. guilty and innocent. Then it is up to those two groups to persuade each other one way or another. Also, a smaller jury pool might allow for someone’s personality to win over some else’s judgement. Not that this don’t happen anyhow, just that with 12 people you are more likely to find someone with a like opinion and you’ll be able to stand with them against the strong personality.

Christopher Allen 2004-03-19T09:42:31-07:00

The applicability of Christopher’s work to analyzing terrorist networks. http://globalguerrillas.typepad.com/globalguerrillas/2004/03/what_is_the_opt.html

John Robb 2004-06-27T11:40:25-07:00

URL: Dunbar’s original work was concerned with social groupings that were effectively the whole of an individual’s “stable relationships”. Ignoring for a moment his insight as to the utility of language in lowering the cost of social grooming, would this not suggest that an individual’s stable relationship total should be aggregated over all groups - so that if you’re in a role-playing guild of, say 70, have a close-knit extended family of, oh, 40, you’re not going be be able to sustain a business (or blog) network of more than about 40. Now, adding language back in should allow these numbers to grow, but I guess the point is that the limit is individual-based, rather than group-based.

Bob Bechtel 2004-07-01T06:38:18-07:00

Someone asked me via email “Is there a format for assessment which you have found useful which you share with others?” I’ve been thinking about assessment, but I’m not sure about how to approach it. One argument is to look at it from an individual perspective. Their approach says that each individual has a max 150 meaningful relationships, so if they have 50 professional relationships, 50 personal relationships, they only have room for relationships with a group of 50 additional people. Thus for you to join another group of 10 you need to triage your existing relationships and drop 10 relationships. The problem with this approach is that although there is probably some truth to it, it doesn’t lend itself to understanding how assess how group works. Does in a new group of 10 each person all only have “room” for 10 more people in each of their networks – that is doubtful. So there must be separate group dynamics involved with group sizes other then just the Dunbar number.

Christopher Allen 2004-07-01T10:06:27-07:00

I have a question about that last graph – the Group Satisfaction one. What is its source? Is it just a visual representation of the anecdotal experience that precedes it? Because if so, it should really be labeled as such. Otherwise it carries the same validity weight as the other graphs, which represented empirical data.

John Tynes 2004-10-13T09:56:55-07:00

You are correct, it of the anecdotal experience. I’ll change the text right above it.

Christopher Allen 2004-10-13T10:34:42-07:00

URL: Dunbar says that human group size, “…would require as much as 42% of the total time budget to be devoted to social grooming.,” and you suggest, “Some organizations will have sufficient incentive to maintain this high level of required socialization,” as long as they’re “…built upon the raw need for survival.” It is interesting in that regard that two groups of professionals who habitually deal with the “raw need for survival,” soldiers and sailors, are often characterized by their love of conversation, “war stories,” “yarning,” and the like, a social-grooming pastime that may approach the percentage of waking hours that Dunbar mentions.

johne 2005-02-07T12:15:50-07:00

Hi Christopher! My groupmates and me are writing a paper about groupsize and leadership. We read your article and we found it very useful for background theory about group size. Can you please tell us if this article has been published somewhere and in which magazine? Thank you! Best regards, Anke Koszczol University of Tilburg Social studies

University of Tilburg 2005-02-28T04:05:35-07:00

Belbin did studies on working groups in the 80s and discovered that there were 8 roles in play and each had its part to play in the group objectives. The best groups were 4 to 8 sized, and the optimal was 4, where each person fulfilled 2 roles. (Of course this was latter statistically unlikely.) Unfortunately, there is very little info on Belbin on the net, as the work is sold as a sort of corporate training aid.

Iang 2005-03-17T15:27:05-07:00

Several comments: - Running live-action role-playing adventures, I have found that the ideal size of an adventuring group is around eight to ten players — this allows for one or two players to hang back and recuperate while the others interact, as it can otherwise be fairly draining to be in character for hours or days at a time, and the interactions get a bit sparse with fewer than six participants. - There is a religious community in Canada that lives together and practices low tech farming. Their farms are not necessarily adjacent to one another, and each farm has up to about 100 members. Whenever a farm begins to approach this limit, it starts the process of splitting in two. This involves working together to acquire a new piece of land, build the new buildings, and prepare everything needed in the new location. The group splits into two, and each chooses a leader. On the night before the move, everyone packs — in both groups. The inhabitants of the new place are not determined until the day of departure. On the morning of the move, the two leaders flip a coin to decide which will go and which will stay. This has the function of investing everyone in the new buildings. In order to replicate this growth strategy, of course, one would have to make sure everyone felt their survival depended on the community, and that they would be willing and able to relocate that investment from time to time. Not so hard online. Rather more difficult in the real world. - Someone is going to start claiming that Dunbar’s analysis doesn’t hold, due to evidence from the recently discovered “hobbits” of Flores Island — comparative complexity of mental capacity in a much smaller brain-case. I offer a pre-emptive counter-argument, in the form of an amendment to Dunbar’s anaylsis. The graph of brain size vs group size might equally well represent brain complexity vs group size. Someone should re-analyze the data on the basis of complexity of the neocortex (or even of the whole brain), rather than its size, in order to back this up.

Gavin Weld White 2005-04-07T16:08:12-07:00

Don’t you think that with the advent of computer technologies, the dunbar number has lost its relavance? I mean with all these modern gadgets like computers and Cable Television, people have lost the will and the art to communicate with others. About 10 Years back, there was enough time after work for members of a family to get together after a hard day’s work to discuss about their current day and have relavent communication. But now there is no time for any communication at all in this fast paced world. And if at all there is time, it is spent in front of the Idiot box (TV) or the more intelligent idiot box (computer) surfing the web. So much for communication!! – http://linuxhelp.blogspot.com

Ravi 2005-05-15T03:27:44-07:00

I guess Judas got cranky being in a group of 13… :-)

Alan R 2006-05-04T11:18:51-07:00

Bless you for this. I have been searching for so long. Now, I need to find fourteen years to study everything you have written so that my questions start to find answers. Thanks sincerely for freely sharing you knowledge.

Amy Stephen 2006-10-13T07:34:49-07:00

URL: I believe the significance of the range of 5 - 9 may come from “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information” (1956) by George A. Miller, cognitive psychologist. Another thought: with language comes the ability to think to oneself, thereby increasing the number of people in one’s tribe by at least one or two (more for Sybil) …

Michael Crowe 2008-04-03T09:32:07-07:00

I was absolutely mesmerized by this blog post, I have to read the others as well! Anyway, so it’s no coincidence the movie is called “12 Angry Men” ( http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0050083/ )? :-)

Carl-Johan Sveningsson 2008-04-04T10:03:46-07:00

URL: Ok, this is ridiculous. Some assertions here must be answered. People can maintain more than 150 relationships. The idea that people can only keep up with 150 people is clearly outside the assertions of Dunbar’s work. Dunbar only says that the maximum sustainable size of a single group is somewhere between 100 and 230 with a 95% confidence. (With the mathematical tendency toward 148.something) This is for a single group with all members fully invested in the group. The real limit in the human mind is the ability to keep track of the relationships between all 150ish people. If the maximum size of a single undivided social network with no outside relationships is 150, his research therefore suggests that the average number of relationships a person can keep track of is 11,175 inter-relationships (1 interrelationship between every possible group of 2 people). It is wrong-headed to say that the limit on a single network of 150 means that someone couldn’t have a network of 50 people in their family network, 70 people in their work network, and another 70 people in their friends network. If these networks are fully separate, then there are only 6,055 total inter-relationships, which lends credence to later research by H. Russell Bernard and Peter Killworth showing the average modern American maintains a social network of mean 290 members (median 231 members).

Echelon 2008-09-30T12:54:07-07:00

Thanks for this writeup on Dunbar’s number, and your scholarship into it. I followed a Twitter message from Luis Suarez to this blog posting. When Malcolm Gladwell was lecturing on “The Tipping Point” at the Rotman School at the University of Toronto, I asked him specifically about the number 150 (in particular, on the Goretex example cited in the book). He didn’t explain that the number 150 was associated with Dunbar, but instead referred to Thomas J. Allen at MIT. I had found a copy of the 1997 book “Managing the Flow of Technology” in an old booksale, which wasn’t very satisfying. I now note that Allen has a 2006 book on “The Organization and Architecture of Innovation” which would be contemporaneous with “The Tipping Point”. Now that you’ve provided with the direct source of the citation, you’ve opened up the academic bottleneck for me. I appreciate your writing.

David Ing 2009-02-12T08:39:57-07:00

It is interesting in that regard that two groups of professionals who habitually deal with the “raw need for survival,” soldiers and sailors, are often characterized by their love of conversation, “war stories,” “yarning,” and the like, a social-grooming pastime that may approach the percentage of waking hours that Dunbar mentions.

Типография 2009-12-26T15:36:20-07:00

URL: What a nice collection of reflections on the Dunbar Number. I would like to add a different formula that I created when studying human groups for my PhD. A = R + (Sq.Rt)M where A = attendance at meetings M = number of formal roles (eg. chair, secretary, coach, etc) M = total number in group membership and of course SqRt is Square Root (won’t use the symbol in case the ascii doesn’t work for anyone) I have found it a pretty good predictor of meeting size all my (post-PhD) life. It is usually more pessimistic that the anticipations of group members that organize the meetings. Sometimes I explain that the best way to increase the attendance is to introduce more (real) roles….. sometimes not, as you are not always thanked for suggestions. I have always felt a fondness for the formula as it is one of the very few non-statistical uses of number in Social Psychology, and it seems a good predictor. For this reason I throw it into the discussion. The original publication was in my PhD 1977 Human Social Groups: A cybernetic account of stability and instability PhD Thesis. Brunel University. and later in book form (now sadly out of print… but I still have some copies if anyone wants one) 1984 Groups John Wiley. Chichester and New York

Mike Robinson 2010-02-24T12:55:43-07:00

Life With Alacrity

© Christopher Allen