(This article has been cross-posted in Medium) Ssh by Katie Tegtmeyer CC-BY (crop2)

Privacy is hitting the headlines more than ever. As computer users are asked to change their passwords again and again in the wake of exploits like Heartbleed and Shellshock, they’re becoming aware of the vulnerability of their online data — a susceptibility that was recently verified by scores of celebrities who had their most intimate photographs stolen.

Any of us could have our privacy violated at any time… but what does that mean exactly?

I think that’s a tricky question, and I say that with decades of experience in the privacy and security fields. In the early ’90s I helped with anti-Clipper Chip activism and supported efforts to allow free export of RSAREF cryptography tools such as PGP. I’m also the co-author of the internet SSL standard, now the most broadly deployed security standard in the world (the “s” in “https”). I’ve been involved with several security companies — as an entrepreneur, a former CTO of Certicom, and most recently as the VP of Developer Relations at Blackphone.

In all that time, I’ve been very careful about my use of the word “privacy”. For example, I founded a company that designed and sold the first commercial SSL toolkits. The technology clearly included privacy features, but our marketing said that SSL offered “message integrity”, “confidentiality” and “authentication”. We did not use the word “privacy”.

This purposeful omission resulted from my feeling that the concept was too overloaded; if I promised privacy I might not be promising the same thing to everyone because people view the term in different ways.

What privacy means varies between Europe and the US, between libertarians and public figures, between the developed world and developing countries, between women and men. I think it’s possible to differentiate no less than four different kinds of privacy, each of which is important to different people — and I’m going to be defining them over the course of this article.

Prelude: Defining Public

However, before you can define privacy, you first have to define its opposite number: what’s public. Meriam-Webster.com’s first definition of “public” includes two different descriptions that are somewhat contradictory. The first is “exposed to general view: open” and the second is “well-known; prominent”.

These definitions are at odds with each other because it’s easy for something to be exposed to view without it being prominent. In fact, that defines a lot of our everyday life. If you have a conversation with a friend in a restaurant or if you do something in your living room with the curtains open or if you write a message for friends on Facebook, you presume that what you’re doing will not be well-known, but it certainly could be open to general view.

So, is it public or is it private?

It turns out that this is a very old question. When talking about recent celebrity photo thefts, Kyle Chayka highlighted the early 20th-century case of Gabrielle Darley Melvin, an ex-prostitute who had been acquitted of murderer. After settling quietly into marriage, Melvin found herself the subject of an unauthorized movie that ripped apart the fabric of her new life. Melvin sued the makers of the film but lost. She was told in the 1931 decision Melvin v. Reid: “When the incidents of a life are so public as to be spread upon a public record they come within the knowledge and into the possession of the public and cease to be private.” So the Supreme Court of Los Angeles had one answer for what was public and what was private.

Melvin’s case was one where public events had clearly entered the public consciousness. However today, more and more of what people once thought of as private is also escaping into the public sphere — and we’re often surprised by it. That’s because we think that private means secret, and it doesn’t; it just means something that isn’t public. Yet. Anil Dash recently discussed this on Medium and he highlighted a few reasons that privacy is rapidly sliding down this slippery slope of publication.

First, companies have financial incentives for making things “well-known” or “prominent”. The 24-hour news cycle is forcing media to report everything, so they’re mobbing celebrities and publishing conversations from Facebook or Twitter that people consider private. Meanwhile, an increasing number of tech companies are mining deep ores of data and selling them to the highest bidder; the more information that they can find, the more they can sell.

Second, technology is making it ridiculously easy to take those situations that are considered “private” despite being “exposed to general view” and making them public. It’s easier than ever to record a conversation, or steal data, or photograph or film through a window, or overhear a discussion. Some of these methods are legal, some aren’t, but they’re all happening — and they seem to be becoming more frequent.

The problem is big enough that governments are passing laws on the topic. In May 2014, the European Court of Justice decreed that people had a “Right to Be Forgotten”: they should be able to remove information about themselves from the public sphere if it’s no longer relevant, making it private once more. Whether this was a good decision remains to be seen, as it’s already resulted in the removal of information that clearly is relevant to the public sphere. In addition, it’s very much at odds with the laws and rights of the United States, especially the free speech clause of the First Amendment. As Jeffrey Toobin said in a recent New Yorker article: “In Europe, the right to privacy trumps freedom of speech; the reverse is true in the United States.”

All of this means that the line between public and private remains as fuzzy as ever.

We have a deep need for the public world: both to be a part of it and to share ourselves with it. However, we also have a deep need for privacy: to keep our information, our households, our activities, and our intimate connections free from general view. In the modern world, drawing the line between these two poles is something that every single person has to consider and manage.

That’s why it’s important that each individual define their own privacy needs — so that they can fight for the kinds of privacy that are important to them.

The First Kind: Defensive Privacy

The first type of privacy is defensive privacy, which protects against transient financial loss resulting from information collection or theft. This is the territory of phishers, conmen, blackmailers, identity thieves, and organized crime. It could also be the purview of governments that seize assets from people or businesses.

An important characteristic of defensive privacy is that any loss is ultimately transitory. A phisher might temporarily access a victim’s bank accounts, or an identity thief might cause problems by taking out new credit in the victim’s name, or a government might confiscate a victim’s assets. However, once a victim’s finances have been lost, and they’ve spent some time clearing the problem up, they can then get back on their feet. The losses also might be recoverable — or if not, at least insurable.

This type of privacy is nonetheless important because assaults against it are very common and the losses can still be very damaging. The latest Bureau of Justice report says that 16.6 million Americans were affected in 2012 by identity theft alone, resulting in $24.7 billion dollars being stolen, or about $1,500 per victim. Though most victims were able to clear up the problems in less than a day, 10% had to spend more than a month.

Though defensive privacy is usually violated by illegal acts, US courts haven’t always recognized the need for privacy of financial records. For example, in the 1976 case United States vs. Miller — which was about defrauding the government of whiskey tax — the Supreme Court declared that an individual’s financial records at a bank were not “private papers” but instead the “business records of the banks”.

It used to be that the biggest danger to defensive privacy was someone digging through a victim’s trash for old bank and credit card statements. However, today the interconnectiveness of the world is making it easier than ever to trick someone out of their financial information. Phishing emails are growing increasingly sophisticated, while social scammers are taking over Facebook and email accounts to pretend to be friends in distress in a foreign country. The newest fad seems to be a resurrection of an old con: cold calling victims and pretending to be Microsoft support in the hope of taking over a victim’s computer.

In other words, defensive privacy is more important than ever — which is unfortunately a trend that crosses all of the kinds of privacy in recent years.

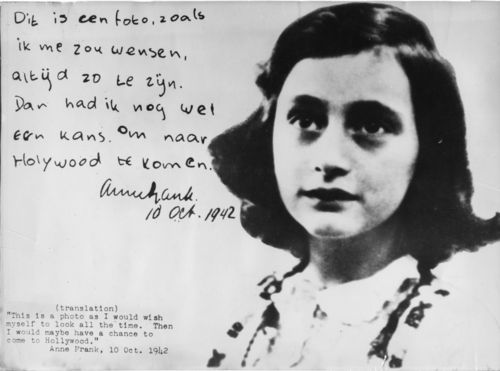

The Second Kind: Human Rights Privacy

The second type of privacy is human rights privacy, which protects against existential threats resulting from information collection or theft. This is the territory of stalkers and other felonious criminals as well as authoritarian governments and other persons intent on doing damage to someone for personal for his or her beliefs or political views.

An important characteristic of human rights privacy is that violations usually result in more long-lasting losses than was the case with defensive privacy. Most obviously, authoritarian governments and hardline theocracies might imprison or kill victims while criminals might murder them. However, political groups could also ostracize or blacklist a victim.

In Europe, human rights privacy is one of the most crucial sorts of privacy. This comes from the continent’s history: the Netherlands in the 1930s had a very comprehensive administrative census and registration of their own population that collected a lot of personal information. The Nazis captured this data within the first three days of occupation. “The Dark Side of Numbers” by William Seltzer and Margo Anderson (published in Social Research Vol. 68 No. 2 — Summer 2001), reports the inevitable result: Dutch Jews had the highest death rate (73 percent) of Jews residing in any occupied Western European country — far higher than the death rate among the Jewish population of Belgium (40 percent) or France (25 percent). Even the death rate in Germany was lower than in the Netherlands because the Jews there had avoided registration.

However, the issue of human rights privacy didn’t end there. As Oxford professor Viktor Mayer-Schönberge explained in Jeffrey Toobin’s New Yorker article, Europe continued to experience serious human rights attacks during the Cold War. Mayer-Schönberge states: “With the Stasi, in East Germany, the task of capturing information and using it to further the power of the state is reintroduced and perfected by the society. So we had two radical ideologies, Fascism and Communism, and both end up with absolutely shockingly tight surveillance states.”

In the United States, citizens are shielded from governmental abuses of human rights privacy by the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. As a result, I personally felt good about human rights privacy in the US — until the presidency of George W. Bush and his first attorney general, John Ashcroft. Under their watch, the Patriot Act dramatically increased the ability of the US government to surveil its citizens, with some of the worst mandates of that law making it illegal for the subject of the surveillance to even talk about being target.

Unfortunately, individuals aren’t the only ones facing the governmental breach of human rights privacy in the US. Ever since the 1972 Supreme Court case, Branzburg v. Hayes, the press has also been fighting against governmental demands to reveal confidential sources and direct governmental assaults on sites like WikiLeaks. Some US states have created shield laws to protect the press’ privacy, but they’re often not sufficient.

Today journalist James Risen faces jail for protecting a source. In a court filing, Risen said “…this court should reconsider Branzburg because in recent years, subpoenas to journalists seeking the identity of confidential sources have ‘become commonplace.’“ The Obama administration responded by stating, “…reporters have no privilege to refuse to provide direct evidence of criminal wrongdoing by confidential sources.” The US Supreme Court refused Risen’s appeal in June 2014, leaving him on the hook for the information or jail time. Meanwhile, other journalists report that surveillance is increasingly intimidating sources, making it hard to report on government activities.

On the bright side, these American governmental excesses are causing some corporations to consider how they can bolster the cause of human rights privacy: with the release of iOS8, Apple announced that they would no longer have access to users’ mobile passcodes, making it nearly impossible for them to turn information over to the government. Google quickly followed on by making Android encryption easier for the public to access. Predictably, the US government isn’t happy, and security experts are nonplussed by their complaints.

Though governments are the biggest actors on the stage of human rights breaches, individuals can also attack this sort of privacy — with cyberbullies being among the prime culprits. Though a bully’s harassment could only involve words, the attackers frequently release personal information about the person they’re harassing, which can cause the bullying to snowball. For example Jessica Logan, Hope Sitwell, and Amanda Todd were bullied after their nude pictures were broadcast, while Tyler Clementi was bullied after a hall-mate streamed video of Clementi kissing another young man. Unfortunately, cyberbullying often results in suicide, showing the existential dangers of these privacy breaches.

Even if threats aren’t taken seriously, cyberbullying doubles back to the issue of defensive privacy, as revealed by Amanda Hess in her article “Why Women Aren’t Welcome on the Internet” where she wrote: “Threats of rape, death, and stalking can overpower our emotional bandwidth, take up our time, and cost us money through legal fees, online protection services, and missed wages.”

Hess is just one of a long list of women who have been targeted by cyberbullies online. Programmer Kathy Sierra was largely driven out of the tech industry back in 2007 for being too influential; she recently wrote about how this is part of a long-standing pattern of purposeful violation.

This year, a study by Pew Research revealed that about 25% of women aged 18–24 have been stalked or sexually harassed online — numbers far in excess of their male peers. It was a timely study because Zoe Quinn, Anita Sarkeesian, and Brianna Wu all came under cyberbullying assault around the same time due to their positions as female leaders in the gaming field. When actress and gamer Felicia Day dared to speak out against this problem, her home address and personal email were revealed in a “doxing” within an hour, showing how fragile privacy is on the modern internet.

It’s not surprising that some of my own female associates are unwilling to post pictures or other personal information online for fear of just this sort of attack. And we’re relatively lucky in the western world: in a hardline theocracy like Afghanistan, a woman’s need for privacy can be even stronger, with many women not willing to use their real names online — or a female name at all.

Individuals taking part in the democratic process can also come under a personal onslaught of this sort. This has gained prominence in California in recent years when numerous people have been called to task over their contributions to Prop 8, an anti-gay-marriage ballot measure that is now widely considered homophobic and bigoted. Brendan Eich, Mozilla’s CEO, was forced out of his job as a result of such a contribution. The fact that his donation was six years previous in a very different political climate shows how long-lasting this sort of damage can be. On the flip-side, the NRA has also been known to go after public figures with anti-gun views. Political repercussions of this sort are a more complex issue than simple cyberbullying, but they demonstrate another situation where individuals might wish they could assert their human rights privacy to shield themselves from damage.

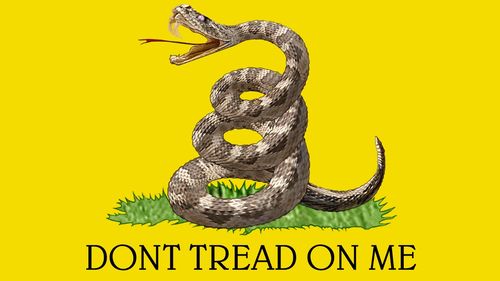

The Third Kind: Personal Privacy

The third type of privacy is personal privacy, which protects persons against observation and intrusion; it’s what Judge Thomas Cooley called “the right to be let alone”, as cited by future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in “The Right to Privacy”, which he wrote for the Harvard Law Review of December 15, 1890. Brandeis’ championing of this sort of privacy would result in a new, uniquely American right that has at times been attributed to the First Amendment (giving freedom of speech within one’s house), the Fourth Amendment (protecting one’s house from search & seizure by the government), and the Fifth Amendment (protecting one’s private house from public use). This right can also be found in state Constitutions, such as the Constitution of California, which promises “safety, happiness, and privacy”.

When personal privacy is breached we can lose our right to be ourselves. Without Brandeis’ protection, we could easily come under Panoptic observation where we could be forced to act unlike ourselves even in our personal lives. Unfortunately, this isn’t just a theory: a recent PEN America survey shows that 1 in 6 authors already self-censor due to NSA surveillance. Worse, it could be damaging: another report shows that unselfconscious time is restorative and that low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety can result from its lack.

Though Brandeis almost single-handedly created personal privacy, it didn’t come easily. The Supreme Court refused to protect it in a 1928 wire-tapping case called Olmstead v. United States; in response, Brandeis wrote a famous dissenting opinion that brought his ideas about privacy into the official record of the Court. Despite this initial loss, personal privacy gained advocates in the Supreme Court over the years, who often referred to Brandeis’ 1890 article. By the 1960s, Brandeis’ ideas were in the mainstream and in the 1967 Supreme Court case Katz v. United States, Olmstead was finally overturned. Though the Court’s opinion said that personal privacy was “left largely to the law of the individual States”, it had clearly become a proper expectation.

The ideas that Brandeis championed about personal privacy are shockingly modern. They focused on the Victorian equivalent of the paparazzi, as Brandeis made clear when he said: “Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life.” He also carefully threaded the interface between public and private, saying, “The right to privacy does not prohibit any publication of matter which is of public or general interest.”

Today, personal privacy is the special concern of the more Libertarian-oriented founders of the Internet, such as Bit Torrent founder Bram Cohen, who demanded the basic human rights “to be free of intruders” and “to privacy”. Personal privacy is more of an issue than ever for celebrities and other public figures, but attacks upon it also touch the personal life of average citizens. It’s the focus of the “do not call” registry and other telemarketing laws and of ordinances outlawing soliciting and trespass. It’s the right at the heart of doing what we please in our own homes — whether it be eating dinner in peace, discussing controversial politics & religion with our close friends, or playing sexual games with our partners.

Though personal privacy has grown in power in America since the 1960s, it’s still under constant attack from the media, telemarketing interests, and the government. Meanwhile, it’s not an absolute across the globe: some cultures, such as those in China and parts of Europe, actively preach against it — advocating that community and sharing trump personal privacy.

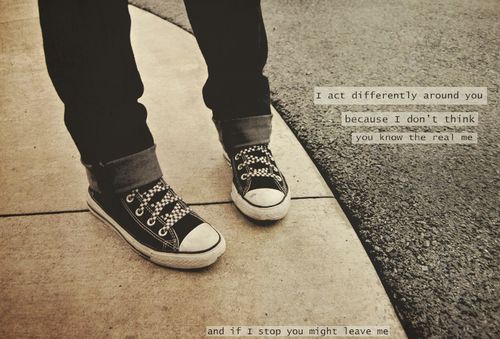

The Fourth Kind: Contextual Privacy

The fourth type of privacy is contextual privacy, which protects persons against unwanted intimacy. This is what danah boyd calls “The Ickiness Factor”:

“Ickiness is the guttural reaction that makes you cringe, scrunch your nose or gasp ‘ick’ simply because there’s something slightly off, something disconcerting, something not socially right about an interaction…. The ickiness factor is tightly coupled with issues [of] feeling vulnerable or getting the sense that someone else is vulnerable because of a given situation.”

Failure to defend contextual privacy can result in the loss of relationships with others. No one presents the same persona in the office as they do when spending time with their kids or even when meeting with other parents. They speak different languages to each of these different “tribes”, and their connection to each tribe could be at risk if they mispoke by putting on the wrong persona or speaking the wrong language at the wrong time. Worse, the harm from this sort of privacy breach may also be increasing in the age of data mining, as bad actors can increasingly put together information from different contexts and twist them into a “complete” picture that simultaneously might be damning and completely false.

Though it’s easy to understand what can be lost with a breach of contextual privacy, the concept can still be confusing because contextual privacy overlaps with other sorts of privacy; it could involve the theft of information or an unwelcome intrusion, but the result is different. Where theft of information might make you feel disadvantaged (if a conman stole your financial information) or endangered (if the government discovered you were whistle blowing), and where an intrusion might make you feel annoyed (if a telemarketer called during dinner), a violation of contextual privacy instead makes you feel emotionally uncomfortable and exposed — or as boyd said, “vulnerable”.

I believe that this feeling of vulnerability often comes from an inappropriate level of intimacy. Some of the more professional social networks seem particularly prone to it: I felt uncomfortable when I realized that my professional colleagues on one of the earliest social networks could see that I was in a committed relationship, and in turn I could see that some of them were in open marriages. Not that I had any problem with the information, but did I “need to know” in the context of business?

You probably won’t find any case law about contextual privacy, because it’s a fairly new concept and because there’s less obvious harm. However social networks from Facebook and LinkedIn to Twitter and LiveJournal are all facing contextual privacy problems as they each try to become the home for all sorts of social interaction. This causes people — in particular women and members of the LGBT communities — to try and keep multiple profiles, only to find “real name” policies working against them.

Meanwhile, some social networks make things worse by creating artificial social pressures to reveal information, as occurs when someone tags you in a Facebook picture or in status update. To date, Google+ is one of the few networks to attempt a solution by creating “circles”, which can be used to precisely specify who in your social network should get each piece of information that you share. However, it’s unclear how many people use this feature. A related feature on Facebook called “Lists” is rarely used.

If a lack of personal privacy causes you to “not be yourself”, a loss of contextual privacy allows other to “not see you as yourself”. You risk being perceived as “other” when your actions are seen out of context.

Case Studies

All four of these kinds of privacy can intersect. For example, some social networks allow you to reveal your sexual orientation, which could be used secretly by an employer to discriminate against you (defensive privacy) or by a future Ashcroftian government to violate your civil rights (human rights privacy). It might lead you to being bothered at home because of people who either agree with or disagree with your orientation (personal privacy) _and often is an inappropriate revelation for casual professional acquaintances (_contextual privacy).

Studies of current events offer more examples.

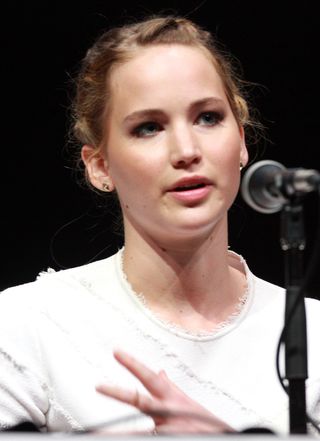

The First Case: Celebrity Hacking

The recent unauthorized release of nude pictures of Jennifer Lawrence and others demonstrates the complex permutations of privacy.

The recent unauthorized release of nude pictures of Jennifer Lawrence and others demonstrates the complex permutations of privacy.

To start with, it highlighted the problematic divide between public and private. There’s no doubt that the pictures were intended to be private, and unlike some of the more troublesome uses of recording devices, these private situations weren’t made public through the uncomfortable use of surveillance technology. Instead, the photos were publicized following theft. Unfortunately, now that they’re in the public eye, they’re unlikely to go away, ever. In other words, the genie’s out of the bottle. All that the celebrities can do is make the photos less accessible by asserting their copyright (if they can to get search engines to de-link the information).

Perhaps Europe’s Right to Be Forgotten will someday help to remove this type of occurrence from the internet. Or perhaps something like California’s recent SB 255 might make it illegal to distribute nude photos without the model’s permission. Alternatively, it could be social mores that win out, if we follow “the ethics of looking away”, as advocated by Jessica Valenti; Jennifer Lawrence herself agreed there are ethical problems, saying: “Anybody who looked at those pictures, you’re perpetuating a sexual offense.” However for now, the pictures are out there and being viewed.

When considering the four kinds of privacy, these celebrities primarily suffered from an unwanted intimacy with the entire world (contextual privacy). Lawrence explained the problem succinctly, saying: “I didn’t tell you that you could look at my naked body.”

Celebrities and other high-profile victims might also face financial repercussions (defensive privacy). Ariana Grande was one of the younger victims of the theft and one of the few to risk the Streisand Effect by saying her photos weren’t authentic. She should never have had to make such a statement one way or the other, but one understands why she would: as a teen pop star recently featured on a pair of Nickelodeon shows, she risks the greatest fiscal damage of any of the victims. But even Lawrence worried, stating: “I didn’t know how this would affect my career.”

Kevin Sullivan offered some of the most adroit commentary on the theft when he said “Don’t call it a scandal”. By calling this a scandal and smugly shaking our heads, we’re blaming the victims, not the criminals. Worse, we’re embarking on a slippery slope where we suggest that people take away their own freedoms through self-censorship. By calling it a scandal, we are saying that even in their own homes, using their own cameras, these people shouldn’t be themselves (personal privacy).

The Second Case: #GamerGate

The widespread and ongoing harassment of game designer Zoe Quinn is a somewhat frightening example for its intense focus on the repeated privacy violations of a single person.

It started with a blog post by Quinn’s ex-boyfriend that accused her of infidelity. This once more highlights the troubled modern divide between public and private. Though some countries might protect the release of information of this sort using defamation laws, it seems unlikely that the US’s slander or libel laws would do so. Despite the likely legality of that initial post, the public still learned inappropriate information about Quinn (contextual privacy).

However, worse privacy violations followed: the online community 4chan doxed Quinn by collecting considerable semi-public information about her (more contextual privacy), which allowed online harassment to evolve into threatening phone calls (human rights privacy). The information revealed during the harassment included the fact that Quinn had dated a game industry journalist, which could impact Quinn’s ability to sell games in the future or even to get reviewed (defensive privacy). Obviously, the continual harassment has also violated Quinn’s personal space and her right to be let alone (personal privacy).

Following the initial assaults on Quinn, the #GamerGate mob has moved on to harass other female game designers, including Anita Sarkeesian and Brianna Wu, as well as gamer and actress Felicia Day — all using the same privacy-busting methodology of cyberbullying and doxing. The movement may have reached its height when terrorist threats were made against a talk planned by Sarkeesian, forcing her to cancel it.

Twenty years ago, it was difficult for groups of individuals to work together to violate the privacy rights of an individual; there also wasn’t a medium that could be used to publish personal details about someone unless there was a clear public interest. The cyberbullying stemming from #GamerGate shows that’s all changed in the modern age. Which is why privacy is such a major concern for so many people on the internet.

The Third Case: The NSA

Though it’s become very easy for individuals to violate the privacy of celebrities like Jennifer Lawrence or individuals like Zoe Quinn, the government has also been stepping up its act in the 21st century, especially since 9/11. In the United States, it’s the NSA who’s been at the heart of the privacy controversies (with a little help from their friends in the FBI).

Many of the new privacy-busting powers of these organizations originated with the USA Patriot Act, but follow-up laws like the Protect America Act of 2007 and the FISA Amendment Act of 2008 are equally invasive. We only know how these laws are actually being utilized thanks to the whistle-blowing of Edward Snowden and others.

Most obviously, these types of laws have allowed the collection of private data in large quantities (human rights privacy). We now know that the NSA uses a previously secret program called PRISM to coordinate data collection using court orders and that they also appear to have broken into communication links to tap major data centers. There are claims that they also exploited the Heartbleed bug for years in order to collect data, though they deny this. The human rights repercussions of this multi-pronged, largely unfettered data collection are mind-boggling.

One of the most worrisome issues with this sort of large-scale data collection is that it can result in mistakes when something is taken out of context (contextual privacy). Someone might feel like they have nothing to fear from the government — until they’re arrested for something they said while roleplaying in an MMORPG. Unfortunately, this isn’t an unfounded concern: Snowden’s whistleblowing revealed that the NSA spies on video game chats!

Meanwhile, this type of contextual disconnect has already caused problems in other legal contexts, such as when firefighter Lt. Philip Lyons was falsely charged with arson based on the purchase of a fire-starter that was revealed through loyalty card records. Reports similarly indicate that the FBI was tracking the sale of Middle Eastern foods in San Francisco as a terrorist-finding tool.

The European Union has much more mature protections against data collection of this sort, thanks to the Data Protection Directive of 1995, which is now in the process of being reformed. Sadly, the US has only responded in a piecemeal way that largely depends on private corporations’ privacy policies.

Returning to the US, we find that many of these data collection and spying laws have been wrapped up with authoritarian regulations that go after individuals — such as one of Edward Snowden’s email providers, LavaBit founder Ladar Levison.

Levison wrote an article about his interactions with the FBI that reads like an Orwellian parody. He described how the FBI served him papers seven times and forced him to appear in a court 1,000 miles from home without an attorney as part of their heavy-handed attempt to acquire Snowden’s encryption keys. His company, LavaBit, was eventually shut down as a result. Because Levison tried to protect the privacy of one of his customers, he was threatened with jail and compelled to silence (personal privacy). Even Yahoo’s CEO Marissa Meyer is personally worried about the trend. She says tech companies aren’t talking more about the government’s surveillance because they’re afraid: “Releasing classified information is treason and you are incarcerated.”

The issue of compelled silence arises from the National Security Letters authorized by the USA Patriot Act. It’s particularly troublesome because it threatens democracy just as much as a lack of voting anonymity would. Because the Letters can’t be discussed, there’s no way to assess whether the government is doing a good job or not — and thus no way to punish a government at the voting booth if they’re stepping over the line.

The Fourth Case: Americans in Afghanistan

My final case study is a personal one. I’ve regularly taught “Digital Influence” and “Using the Social Web for Social Change” classes in the Bainbridge Graduate Institute’s MBA in Sustainable Systems program at Pinchot University. One of my students there was Luisa Walmsley.

While at BGI, Luisa met a woman who had co-founded Afghanistan’s largest telecommunications company. Luisa later went to work at the company, then started her own consultancy doing operations and business development for Afghan media and technology companies — in the process helping women in Afghanistan to become better entrepreneurs. She’s also been involved with Afghanistan’s first-ever social media summit.

Unfortunately, being a female professional in Afghanistan can still be quite dangerous. Women have only been able to widely reenter the work force in the last decade, since the 2001 overthrow of the Taliban, and today they are sometimes still attacked or threatened for doing so. This makes Luisa’s need for privacy important (human rights privacy).

Luisa’s situation also demonstrates the sorts of divides you can find in a human rights privacy case. While in Afghanistan, Luisa follows basic security procedures to protect her privacy from both terrorists and the government — such as varying the times of day that she travels to the office. She’s still willing to use social media but is careful, for example occasionally lying about her location or not talking about her travel plans or waiting days to post pictures that might reveal information as to her whereabouts. However Luisa has to be even more careful with the human rights concerns of the women she’s working with, who could be assaulted or killed for their decision to make a career for themselves.

Even outside of her work proper, Luisa has run into other sorts of privacy issues in Afghanistan. She was once asked by an Afghan government agency to remove a Facebook post that reprinted an international organization’s security alert concerning elections security, which she’d reposted in order to warn her friends. She’s also received phone harassment (personal privacy) that would be unthinkable in the US: in Afghanistan men cold call phone numbers and when they hear a woman’s voice on the other side, they continuously call back. Luisa was often able to stop the calls, but some of her female friends would receive over 200 harassing phone calls of this sort a day.

Unfortunately, Luisa’s work also runs straight back into the privacy problems originating with the NSA. In 2013, the NSA admitted that they tracked phone calls of people “two to three hops” away from suspected terrorists. However in Afghanistan, everyone working in human rights or in the media is going to have some direct contact with the Taliban. Luisa surely has (one hop), so as soon as she calls or emails me (two hops), I’m suddenly in the NSA jackpot (more human rights privacy). And how does the NSA get that information? In 2014 we learned that they’re recording nearly all domestic and international phone calls in Afghanistan (massive human rights privacy).

Because we know that the FBI once though it was relevant to track falafel sales, and because I gained an appreciation for Middle Eastern music 15 years ago, I could easily become a serious terror suspect myself (yet more human rights privacy). Worse, if you’re reading this article (three hops), you now might be in the NSA’s sights too. Hope you don’t like hummus or baba ghannouj!

Conclusion

Privacy is important — perhaps more so than ever due to the assaults by con artists, governments, the press, and social media in the 21st century. However, in order to protect your own privacy, you must define your terms.

First, that requires: understanding the difference between private and public; considering how to prevent information from escaping from the one to the other; and thinking about how that might interact with free speech.

Second, it requires understanding the different kinds of privacy, and figuring out which one is most topical to you.

• Is it defensive privacy?_ W_here you worry about conmen, phishers, or other thieves stealing from you? Do you fear the finances loss?

• Is it human rights privacy?_ W_here you’re threatened by the actions of a government or other entity? Do you fear the loss of your life or your freedom?

• Is it personal privacy? Where you just want to be be left alone? Do you fear the loss of the freedom to be yourself?

• Is it contextual privacy? Where you want to partition different portions of your life? Do you fear the loss of your relationships?

Most people will have some concerns about multiple sorts of privacy, but there will probably be one or two that strike a chord.

So what’s important to you?

About the Author

Christopher Allen is a technologist and entrepreneur with a long history of work in the privacy and security fields. As the founder of Consensus Development, he led and co-authored the IETF-TLS (SSL 3.0) standard and sold the first commercial SSL toolkits. He’s also the former CTO of the cryptographic security company Certicom (now part of Blackberry). Recently he was VP of Developer Relations for the secure smartphone company Blackphone, building on his experience with mobile software industry . He has produced a number of iOS apps, spoken at conferences, and organizes developer hackathons at such events as iOSDevCamp. Christopher also teaches Technology Leadership in the MBA in Sustainable Systems program at Bainbridge Graduate Institute at Pinchot University.

This article is based on an original post written in 2004 in Christopher’s blog Life With Alacrity, and presentations on the topic of privacy used in his classes and posted at slideshare.net.

Image Credits

Cover Image is cropped from Katie Tegtmeyer’s “Talk Shows on Mute” from Flickr, and is licensed CC-BY.

Public is cropped from Mike Baird’s “July 4th Parrade in Cayucos, CA” from Flickr, and is licensed CC-BY.

Defensive Privacy is cropped from Christophe Verdier’s “Day 342 — Hacker” from Flickr, and is licensed CC-BY-NC.

Human Rights Privacy is from an image in Ann Frank Diary, and is offered under fair use.

Personal Privacy is cropped from DonkeyHotey’s “Dont Tread on Me” on Flickr, and is licensed CC-BY-SA.

Contextual Privacy is from Meg Willis’s “Post Secret #2” from Flickr and is licensed CC-BY.

Portrait of Jennifer Lawrence is by Gage Skidmore “Jennifer Lawrence SDCC 2013 X-Men” from Japanese Wikipedia and is licensed CC-BY-SA.

Self Portrait of Zoe Quinn is by Zoe Quinn from Wikipedia and is licensed CC-BY-SA.

NSA Seal is from converted from svg image on Wikipedia and is Public Domain.

Portrait of Ladar Levison is cropped from a photo by Joe Paglieri from CNN Money, and is offered under fair use.

Luisa Walmsley at Afgan Social Media Summit is cropped from a photo by Luisa Whalmsey and is licensed CC-BY.

Appendices & Bibliography

See the following post The Four Kinds of Privacy: Appendices & Bibliography.

Life With Alacrity

© Christopher Allen